| and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT while she whispered a song along the keyboard to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing |

Thursday, April 12, 2012

National Poetry Month/ Erratum

National Poetry Month

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT while she whispered a song along the keyboard to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathingNow this is an economics blog, so for National Poetry Month I will append another of my favorite poems, large portions of which I have excerpted in an article I wrote for JEI lo these many years ago. It is Elizabeth Bishop's "Crusoe in England."

| Crusoe in England A new volcano has erupted, Well, I had fifty-two My island seemed to be I often gave way to self-pity. The sun set in the sea; the same odd sun Because I didn't know enough. The island smelled of goat and guano. Dreams were the worst. Of course I dreamed of food Just when I thought I couldn't stand it And then one day they came and took us off. Now I live here, another island, The local museum's asked me to |

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Very Positive Review of The Invention of Capitalism

Our popular economic wisdom says that capitalism equals freedom and free societies, right? Well, if you ever suspected that the logic is full of shit, then I’d recommend checking a book called The Invention of Capitalism, written by an economic historian named Michael Perelman, who’s been exiled to Chico State, a redneck college in rural California, for his lack of freemarket friendliness. And Perelman has been putting his time in exile to damn good use, digging deep into the works and correspondence of Adam Smith and his contemporaries to write a history of the creation of capitalism that goes beyond superficial The Wealth of Nations fairy tale and straight to the source, allowing you to read the early capitalists, economists, philosophers, clergymen and statesmen in their own words. And it ain’t pretty.

More at:

http://exiledonline.com/recovered-economic-history-everyone-but-an-idiot-knows-that-the-lower-classes-must-be-kept-poor-or-they-will-never-be-industrious/

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Robert Samuelson Again In Deep Doo Doo On Social Security

Samuelson's new claim is that FDR would not like the current Social Security system, presumably because it is heading for being "broke" someday (eeeek!), as Samuelson periodically likes to moan and groan about. However, as he has often done in the past and is noted by all three of the above, he pulls a bait and switch, starting out with the usual grumbling over the gradually rising and well known rise of the worker-retiree ratio (likely to hit in 2025 or so the ratio Germany already has, eeeek!). Then he throws out some awful fiscal numbers, but it turns out that he has dragged in without making any serious comment on it Medicare and Medicaid expenses as well as those for Social Security, then concluding how something must be done about Social Security now! It is of course these latter two whose projected rising costs are really the problem.

It is true that the projections for SS do not look as rosy as they did some years ago prior to the Great Recession. But, even with the lower projections now, there is no clear problem until maybe in the late 2030s. Even then, assuming no fixes, the terrible thing that might happen, with Krugman picking up on something that I and Bruce Webb have been pointing out for years, is that the benefits might drop to a level that would be still well above current benefits in real terms (eeeeeek!). Krugman also makes the reasonable point we have that what Samuelson is suggesting is that future benefits should definitely be cut now, because if they are not, future benefits might get cut in the future. Yes, that is the ridiculous illogic of much of this discussion by "Serious People."

Let me add on to this two points, also floating around in the econoblogosphere. One is this matter of self-important centrism. So, people like Samuelson wish to present themselves as the late David Broder did as centrist Serious People who are between the right and the left. So, they have to find fault with programs supposedly of both sides. In many cases, particularly Samuelson's, although it has been a vice of many WaPo commentators for a long time as Dean Baker notes, they like to whomp on and on about Social Security and how we need to cut future benefits now.

The other matter that has me seriously concerned is that this renewed push by SS critics like RJS is that this coincides with the mangled and awful discussions going about the Ryan budget. Again, Krugman is right to point out that the loud centrists have seriously hung their hats on Ryan being reasonable, so that there is this unwillingness to confront the fact that his budget combines a lack of detail on just how tax loopholes are to be closed along with a lack of detail on how deep those non-defense cuts will be, although he has been declaring that they will not hurt the poor and will be no worse than welfare "reform," which has failed to help the poor at all during this Great Recession (and is also now apparently claiming that he is for all this thanks to his Catholic background, ignoring the Church's opposition to what his budget proposes). Given the need to fight all the obfuscations going on by so many to make Ryan look reasonable, it is easy for people like Samuelson to start peddling their baloney again about Social Security under the radar.

It is really frustrating how this garbage just does not seem to stop, but calling it out when it rears its ugly head is what we must continue to do.

The Bush Boom?

Spencer seems to be an Angry Bear over some chart from Greg Mankiw – and maybe he should be:

I see that his blog Mankiw shows a chart of the employment population ratio to make a comment about the "so called recovery". But he selected the start date of the chart so that you could not see that during the eight years of the Bush administration the employment-population fell from 63.0 to 60.3, a 2.7 drop. Since Obama took office the employment-population fell from 60.3 to 58.6, a 1.7 drop. The ratio has done poorly under both administrations, but people who live in glass houses should be careful about throwing rocks.

Our graph of the employment to population ratio goes from January 1998 to December 2008. It actually shows that the employment to population ratio when Bush took office was 64.4%. Of course we had a recession right after that followed by a recovery that managed to get this ratio back to 63.4% before the Great Recession that started in December 2007 leading to a collapse in the employment to population. Neither economic growth nor employment did all that well during Bush’s Presidency and yet the usual suspects are hanging out at the Bush Institute lecturing to us about how their policies might someday magically lead to 4% long-term growth.

But let’s be honest – this is an awfully slow recovery. I would argue the reason for this is a lack of fiscal stimulus as demonstrated in our first graph showing real government purchases. Of course, Team Republican wants us to believe that we have too much government spending. I wish one of the actual economists on Team Republican would be candid enough to admit that days after Barack Obama was elected President he called for a much more vigorous stimulus policy only to find that Mitch McConnell would choose to filibuster this proposal to death. Then again – such honesty would get one kicked off Team Republican.

Monday, April 9, 2012

The Bush Institute Hosts Tax Policies for 4% Growth?

The 4% Growth Project was launched by the Bush Institute in 2011 with the goal of achieving sustainable and real GDP growth of four percent, an attainable level that will ensure Americans of better jobs, lower debt, and vastly increased opportunity and prosperity. Through this conference and other events, the 4% Growth Project will identify changes in government policy and business practices that will produce higher growth and advocate those changes to policy makers and the public. The aim of this conference, as well, is to change the economic conversation in America so that it focuses on growth and what causes it.

With speakers such as Steve Forbes, Paul Gigot, Paul Ryan, Amity Shlaes, John Stossel, and Lawrence Kudlow – I’m not wasting my time either. But let’s recall how well the economy grew during the Administration of George W. Bush over its first seven years (with 2008 being the advent of the Great Recession) – an average annual growth rate less than 2.4%. Now we did have this crowd in power from 1981 to 1992 when the economy grew at an amazing 3% per year. I guess they believe the third time will be the charm?

Declining Education Spending

Via Paul Krugman, Manny Fernandez writes about the effects of budget cuts for schools in Texas.

Table 3.15.6 of the National Income and Product Accounts ala BEA provides information on Real Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment by Function showing education spending (in 2005$) from 2003 to 2010. Our chart shows real education spending, which unfortunately has been declining since 2008. The vast majority of this spending comes from state and local government and the declines have been across the board: elementary/secondary spending, spending on higher education, and spending on libraries. No – we can’t blame the unions for the Herbert Hoover style fiscal policies of many of our state and local governments.

Friday, April 6, 2012

Herb Gintis on Evolution and Morality

Which Way for the World Bank?

I’ve seen two general themes in discussions about the three-way race for World Bank president. One is about the pledge to open up the process, fairly and transparently, to all candidates from all countries by jettisoning the custom that the US picks the top post at the Bank, while Europe gets the IMF. This is long overdue; does anyone openly defend the US prerogative? The second is about experience and bureaucratic savoir-faire; Jim Kim, the US pick, is obviously untested in the sort of organizational leadership challenges that await him at the Bank if he gets the job. The other two, Colombia’s Ocampo and Nigeria’s Okonjo-Iweala, have more relevant profiles.

But there is a third, overarching issue, perhaps the biggest of all: what is the position of the World Bank, and its sister Bretton Woods spawn, the IMF, in the framework of global governance? In particular, what is its relationship to the UN system and the global partnerships that have spun off from it? In a way, this is the same as issue #1, but it is much more encompassing and involves substance as well as process.

The UN system—by which I mean the many specialized UN agencies, and not primarily the security apparatus housed in New York—is relatively democratic in the world of states: the richest countries do not rule by themselves but must find agreement with the others. From time to time, for instance, a dispute flairs up in which UNESCO or some other agency annoys the US. Americans withhold money, perhaps even withdraw, but the agency goes on, modified perhaps but not subservient. If you read the agenda documents of these agencies, they are generally far to the left of the permissible space given to US politics, and on the leftward side of political space in Europe.

The Bank and the Fund, on the other hand, are largely controlled by the richest countries, and even within that sphere, by the US and the EU. Their stated goals have historically been further to the right, sometimes directly conservative, as in their espousal of labor market “flexibility” and financial liberalization.

The split between the two international systems reached its peak during the Washington Consensus years of the 1990s, when the Bretton Woods twins (and their younger sibling, the WTO) were steeped in orthodoxy. Since then there has been a partial rapprochement. After the East Asian financial crisis the Fund retreated from its taboo against any form of capital controls, for instance, and the Bank’s embrace of the Millennium Development Goals symbolized its new openness to UN-ish progressivism. In recent years this shift has become even clearer. The IMF is now, astonishingly, a voice for relative fiscal heterodoxy, particularly in the European context, while the Bank has broken from its erstwhile endorsement of fees for education and health, and has participated in the Leading Group on Innovative Financing and, more recently, the Social Protection Floor Initiative. One should not exaggerate, however, since there remains a significant gap between Bretton Woods and San Francisco (the UN). Joint work often requires compromise: one example is the restriction of the MDG education targets to primary education only. This reflects the Bank’s view at the time, and, in my opinion, it is symptomatic of a narrow, even paternalistic approach to development.

So what now? At least as far as perceptions are concerned, both Kim and Ocampo favor even further movement toward a UN-centered conception of the Bank’s objectives; in fact, both have UN backgrounds. To be honest, I was surprised at Kim’s selection by Obama, since the Obama administration has been hostile to much of the UN agenda, such as the program of the Leading Group. It almost looks like a mistake. In any case, if either of these two is ultimately chosen, there will be more impetus for tying the bank more closely to the UN. On the other hand, and again from the vantage point of perceptions, Okonjo-Iweala is the insider candidate, more oriented to maintaining the Bank’s existing priorities and less open to the UN.

I will be honest and say that I have no basis for predicting how these three individuals would actually perform in office. Maybe the perceptions are right, and maybe they aren’t. Nevertheless, I think it’s useful to see the politics of these two branches of global governance clearly; how they evolve is what matters and not the optics of who is from where or what their last job was.

Disclosure: I have done a lot of work with the International Labor Organization, a branch of the UN system, over the years. I like and respect the individual Bank people I have worked with, but sometimes the political gap between their outfit and mine has been a problem.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

In the Blogosphere, Econ Looks Macro

I’m mainly a microeconomist. There are lots of folks like me. I don’t know the percentages, but surely microeconomists make up a large proportion of the global econ profession. Lots of important ideas and empirical discoveries are flowing through the micro pipeline all the time.

Yet if you didn’t know anything else about economics other than what you read in the blogosphere, you’d think that most economists were on the macro side, that the main schools of thought in macro determine how we are sorted intellectually, that the real-world importance of economics is mainly about economic growth, employment, inflation, etc., and that macro is where the new ideas are.

How come? Is it because the financial crisis and its global consequences, like the bitter politics of fiscal budgets, are currently at center stage? Or because the news cycle in macro is so much faster, with new data points popping up every day? Or is it because the ideological implications of macroeconomic disputes are more apparent than most micro dustups? Or because key players, like Mark Thoma (who should wear a headband saying “I am a public good”) and Paul Krugman, are mainly macro?

Actually, there are huge things happening on the micro side of the aisle. Climate change remains one of the world’s fundamental challenges, the battle against mass poverty has taken a micro-ish turn, and a slow-mo intellectual drama of vast significance is taking place in welfare economics—it’s crumbling under the weight of behavioral econ and related threats. Applied micro is largely on autopilot, so theoretical developments are mostly out of view, but the whole idea of the blogosphere is that everything is potentially in view.

How do we get to where millions of online readers feel the day is not complete without a dose of microeconomic controversy, or that their vocabulary is missing something if it doesn’t include network externalities and subgame perfection?

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Feldstein v. Lazear on the Size of the Output Gap

Here is what worries me: the structure of US unemployment is very different in the current downturn than it was in the past. Nearly half of the unemployed have been out of work for six months or longer. In the past, the corresponding unemployment duration was only 10 weeks. So there is a danger that the long-term unemployed will be re-employed much more slowly than in previous recoveries. If the unemployment rate is still very high when product markets begin to tighten, the US Congress will want the Fed to allow more rapid growth in order to bring it down, despite the resulting risk to inflation. The Fed is technically accountable to Congress, which could apply pressure on the Fed by threatening to reduce its independence. So inflation is a risk, even if it is not inevitable. The large volume of reserves, together with the liquidity created by quantitative easing and Operation Twist, makes that risk greater. It will take skill – as well as political courage – for the Fed to avoid the rise in inflation that the existing liquidity has created.

Dr. Feldstein is implicitly saying that the GDP gap is not as large as what Ed Lazear wants us to believe:

During the postwar period up to the current recession (1947-2007), the average annual growth rate for the U.S. was 3.4%. The last three decades have experienced somewhat slower growth than the earlier periods, but even in the period 1977-2007, the average growth rate was 3%. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the recovery began in the second half of 2009. Since that time, the economy has grown at 2.4%, below our long-term trend by either measure. At this point, the economy is 12% smaller than it would have been had we stayed on trend growth since 2007. Worse, the gap is growing over time. Today, the economy is four percentage points further from the trend line than it was the first quarter of 2009 when this administration's nearly $900 billion fiscal stimulus efforts began. If forecasts of around 2% growth turn out to be accurate, we will add to that gap this year.

Lazear wants us to believe that the economy could have continued to grow by 3.4% per year since 2007QIV even though average growth was less than 2.5% for the 2001 to 2007 period. If that claim had any credence then potential real GDP would have been almost $15.3 trillion as of 2011QIV as opposed to actual real GDP being only $13.4 trillion. In other words, Lazear wants us to believe that the current GDP gap is 12%. Not that anyone should believe such nonsense but isn’t it interesting that Dr. Feldstein is worried that we may be overestimating the GDP gap.

Republicans are simultaneously pushing two themes. One theme is that current Federal Reserve policy is endangering an inflationary spiral, which seems to be the concern of Dr. Feldstein. The other theme is that the Obama Administration is somehow making the recession worse, which Dr. Lazear was so happy to echo. Funny thing – these two themes appear to be contradictory.

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Ed Lazear Takes One For Team Republican

During the postwar period up to the current recession (1947-2007), the average annual growth rate for the U.S. was 3.4%. The last three decades have experienced somewhat slower growth than the earlier periods, but even in the period 1977-2007, the average growth rate was 3%. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the recovery began in the second half of 2009. Since that time, the economy has grown at 2.4%, below our long-term trend by either measure. At this point, the economy is 12% smaller than it would have been had we stayed on trend growth since 2007. Worse, the gap is growing over time. Today, the economy is four percentage points further from the trend line than it was the first quarter of 2009 when this administration's nearly $900 billion fiscal stimulus efforts began. If forecasts of around 2% growth turn out to be accurate, we will add to that gap this year.

Brad does not buy this 3.4% per year increase in potential real GDP, which is not consistent with what CBO is telling us. Using the FRED database, one can calculate the percentage difference between CBO’s measure of potential GDP versus actual GDP. By mid-2009, this gap had grown to 7.4%. Since then it has slowly declined to around 5.5%.

But hey – we are indeed far from full employment in my opinion. Item #2:

Are there other factors that may have contributed to the slow recovery that we are experiencing? It would be difficult to argue that government polices over the past three years have enhanced confidence in the U.S. business environment. Threats of higher taxes, the constantly increasing regulatory burden, the failure to pursue an aggressive trade policy that will open markets to U.S. exports, and the enormous increase in government spending all are growth impediments. Policies have focused on short-run changes and gimmicks—recall cash for clunkers and first-time home buyer credits—rather than on creating conditions that are favorable to investment that raise productivity and wages.

Aha – the standard GOP talking points! What enormous increase in government spending? Excuse this Keynesian for suggesting that we’ve had too little fiscal stimulus.

The New York Times and Romney: Lost and Without a Clue

The New York Times tried to play gotcha today with Mitt Romney and displayed truly awful journalism. How clever we are, they thought: we will show that Romney’s position on energy in 2012 is different from the one he laid out in his book in 2010. Isn’t this what tough, gritty reporting is all about?

No, it isn’t. The whole attack is misguided, since reasonable people change their minds about things all the time, even if they can’t admit it while they are running for president. Unreasonable people also change their minds, or never had a mind in the first place, but inconsistency doesn’t help you figure out who they are. Readers of this supposedly serious analysis will learn exactly nothing of value.

Meanwhile, here is what the article didn’t say: it is an unquestionable fact that neither Obama nor Romney have it within their power to alter the market price of oil. The fact that oil prices have risen by more than a third in the last two years has zilch to do with government policy. The whole “issue” is stupid.

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Lost Hours

Those were the hours I spent reading Lost Decades, by Menzie Chinn and Jeff Frieden. I had high hopes for this book because of the obvious skills of its authors, and I was scouting it out as a possible text for my class on the financial crisis next fall.

Not a chance.

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Unpacking the Decoupling Tautology

The Sandwichman is concerned with another kind of decoupling -- the much touted decoupling of energy consumption from GDP growth that technological optimists like Amory Lovins promote as the solution to environmental impact and resource exhaustion problems. Relative decoupling of energy consumption per dollar of GDP is a well established fact. What is in dispute is whether that can be translated into absolute decoupling through imminent technological breakthroughs.

The short answer is: it can't. The slightly longer answer is it can't because even the relative decoupling that has occurred over the last 39 years is questionable. Oh, there's no doubt that energy consumption per dollar of GDP has fallen; what's questionable is the composition and distribution of that growing GDP.

Even at the aggregate level, there is the question of the increasing proportion of economic activity that needs to be devoted to repairing the damage done by previous economic activity -- cleaning up toxic spills, recovering from extreme weather events, etc. This is what Stefano Bartolini referred to as negative externalities growth and Roefie Hueting called asymmetric entering. This is a kind of decoupling of GDP increase from any meaningful notion of expanded or improved utility. It is just running faster on a treadmill.

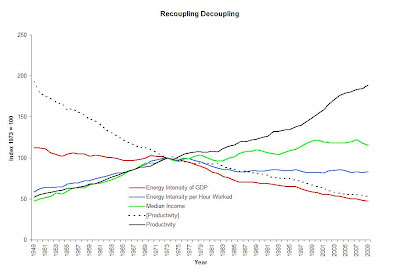

But that's not all. There is also the question of distribution and even the possibility that the growing gap between GDP growth and median incomes is a structural imperative. Now, by "structural imperative" I don't mean something that can't be changed -- only something that isn't going to be budged by moralistic pronouncements about fairness. To show what I mean by structural imperative, I would like to share a composite chart that integrates the data from the EPI productivity and median income chart above and data comparing the energy intensity of GDP to the energy intensity per hour of work. I have added an inverted productivity series (black dotted line) for reasons that will become clear as the narrative unfolds.

|

| Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Energy Information Agency, U.S. Census Bureau |

The first thing that becomes clear from this chart is that productivity, median income and the energy intensity per hour worked tracked each other closely from 1949 to 1973. The latter year was chosen as the index year because energy intensity per hour of work peaked in that year. After 1973, energy intensity per hour of work declined for about ten years and then remained virtually flat up to the present. Productivity and Median Income diverge after 1973.

The inverted productivity series now presents a clue as to what exactly is being "decoupled" in all this decoupling. With productivity defined as GDP per hour worked, inverted productivity is hours worked per unit of GDP. Before 1973, inverted productivity appears as simply the mirror image of productivity, median income and energy intensity per hour worked. After 1973, though, it tracks energy intensity of GDP, while the stable energy intensity of hours worked can be understood as the axis around which productivity and energy intensity of GDP rotate and reflect one another. For all intents and purposes, then, one could say that "energy intensity of GDP" is a statistical tautology, which itself, prior to 1973, performed as the axis around which productivity growth translated into steady gains in median income.

Correlation does not imply causation. Sometimes, however, it reveals a hidden tautology. Hours, energy consumption, income and GDP are inputs and outputs of an economic system that transforms some of those into some of these. The inputs don't cause the outputs any more that cattle "cause" beef, they're just different names for the same thing in a different state.

The indexes I have plotted in the graph are ratios between inputs and outputs (productivity and energy intensity of GDP) or inputs and other inputs (hours of work and energy consumption). Median family income can be thought of as a circular ratio of inputs and outputs in which both income and the family can be viewed alternatively as either outputs or inputs -- income provides sustenance for the family; the family supplies labor to industry in return for income and so on.

Ratios between inputs do not wholly determine ratios between outputs or between inputs and outputs. Policies do that. But the quantities of outputs are constrained by the quantities of inputs. It is thus necessary when examining the energy intensity of GDP, for example, to ask what is happening with the other inputs and the other outputs.

In closing, I would like to present a third chart that compares the growth of population, labor force, employment and hours worked in the U.S. from 1950 to 2009.

When I initially chose employment as the numerator of an alternative index, I was aware that there was a rough coincidence with total population and thus would be similar to a per capita energy consumption index but would smooth out some of the cyclical variations. Aggregate hours of work presumably performs this smoothing function even more precisely. For the last fifty years, though, the growth in employment, labor force and aggregate hours has been steeper than population growth, with hours reaching a peak in 2000 of nearly 30% more per capita than in 1961. Employment as a percentage of total population peaked in 2008, even though labor force participation peaked in 2000 because the later ratio considers only the population 16 years and older.