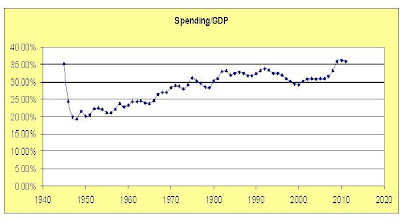

he insisted (if I understood him correctly) that currency debasement and price controls destroyed the Roman Empire. I responded that I am not a defender of the economic policies of the Emperor Diocletian.I studied ancient history as well as economics in college but I don’t profess to know much about the policies of Emperor Diocletian either. Paul’s performance was strange in so many ways. For example, he pretended to be the defender of free markets as accused Dr. Krugman of not being in favor of market based economies. Yet, Ron Paul was the one who does not want the market to determine exchange rates, which is just one of many ways we know he is not very familiar with the writings of Milton Friedman. I guess there was one subtle point of concession between the two debaters. Both seemed to think the economy that followed World War II was a good one. But Ron Paul’s praise of this period struck me as odd as he claimed that the reason that the government debt to GDP ratio fell was an alleged decline in government spending. Our graph does show that government spending as a share of GDP was still high in 1945 so this ratio had to decline as we reduced defense spending as World War II ended. But our graph shows that government spending rose as a share of GDP for much of the latter half of last century. So maybe Ron Paul knows more about the Roman Empire than I do but his knowledge of recent history is suspect.

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

Ron Paul Praises the Post World War II Economy for Its Reduction in Government Spending

Paul Krugman notes his debate with Ron Paul:

Monday, April 30, 2012

Robert Samuelson Playing Anti-Robin Hood Again

In today's Washington Post, Robert J. Samuelson is at it again with a column called "The real Washington," in which he admonishes his readers for not realizing that we are a democracy and that the rich are paying for huge increases in aid to the poor, up from $126 billion in 1980 in real terms to $626 billion today, even while the suffering top income quintile are supposedly paying "70%" of federal taxes, poor things. He clearly decries this and thinks that aid to the poor along with his usual favorite target, Social Security, should if not be cut at least capped. The rich ae doing enough, more than enough, poor things, and here we are facing the "terrible threat of long term deficits," even though he only once manages to mention that "More promises were made than can be kept without raising taxes, which -- for the most part -- were also subject to bipartisan promises against increases." That this last remark is ridiculously lopsided should go without saying, but RJS is keen to maintain his position as a Very Serious Centrist.

Dean Baker does a good job on pulling some of this mess apart, pointing out how much income has concentrated to the very top of the income distribution, with RJS emphasizing the top 20% rather than the top 1% or top 1/10% - http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/the-power-of-the-rich-is-measured-by -their-income-not-just-their-taxes . Anyway, even looking at RJS's numbers, they are not as dramatic as they look. While indeed the top quintile does pay 67.2% of federal taxes (not RJS's apparently rounded off 70%), the same top quintile earns 53.4% of income. So, yes, indeed, the federal tax code is mildly progressive. But in fact it used to be more so than it is now. The average federal tax rate for that top quintile has been lower since 2001 than it was for any years since the end of WW II except for 1982 and 1983. This moaning about the poor rich on taxes just looks silly.

Furthermore, RJS's numbers overstate what has gone on regarding aid for the poor. Yes, indeed, it has indeed risen in real terms since 1980. But this increase is certainly overstated. The problem as almost always with RJS is that he ignores the outsize price increases in healthcare costs. His calculation of real payments seems to be deflated by the general CPI rather than the sector-specific ones. While from 1980 to 2010, the overall CPI rose 141%, the medical care one has risen 394%. The 1980 "real" number for Medicaid was about $60 billion, rising to $275 billion in 2011 out of the $621 billion for the poor. This seems like a massive increase, but when one corrects for the far greater increase in medical care costs than overall prices, the real increase in this is relatively modest, and this increase supposedly constitutes nearly half the overall increase.

While we are at it, expenditures on TANF have not risen since welfare reform, and the number of enrollees has barely budged during the Great Recession. This part of the system for helping the poor has been nearly useless in the recent crisis. I am glad that food stamps (SNAP) have been way up, but Samuelson is just missing it when he tries to paint a picture of the rich being snagged badly by a bunch of overcovered poor people (along with ignoring the skewing to the rich of the tax code, not to mention the role of rising medical care costs in the spending patterns).

Dean Baker does a good job on pulling some of this mess apart, pointing out how much income has concentrated to the very top of the income distribution, with RJS emphasizing the top 20% rather than the top 1% or top 1/10% - http://www.cepr.net/index.php/blogs/beat-the-press/the-power-of-the-rich-is-measured-by -their-income-not-just-their-taxes . Anyway, even looking at RJS's numbers, they are not as dramatic as they look. While indeed the top quintile does pay 67.2% of federal taxes (not RJS's apparently rounded off 70%), the same top quintile earns 53.4% of income. So, yes, indeed, the federal tax code is mildly progressive. But in fact it used to be more so than it is now. The average federal tax rate for that top quintile has been lower since 2001 than it was for any years since the end of WW II except for 1982 and 1983. This moaning about the poor rich on taxes just looks silly.

Furthermore, RJS's numbers overstate what has gone on regarding aid for the poor. Yes, indeed, it has indeed risen in real terms since 1980. But this increase is certainly overstated. The problem as almost always with RJS is that he ignores the outsize price increases in healthcare costs. His calculation of real payments seems to be deflated by the general CPI rather than the sector-specific ones. While from 1980 to 2010, the overall CPI rose 141%, the medical care one has risen 394%. The 1980 "real" number for Medicaid was about $60 billion, rising to $275 billion in 2011 out of the $621 billion for the poor. This seems like a massive increase, but when one corrects for the far greater increase in medical care costs than overall prices, the real increase in this is relatively modest, and this increase supposedly constitutes nearly half the overall increase.

While we are at it, expenditures on TANF have not risen since welfare reform, and the number of enrollees has barely budged during the Great Recession. This part of the system for helping the poor has been nearly useless in the recent crisis. I am glad that food stamps (SNAP) have been way up, but Samuelson is just missing it when he tries to paint a picture of the rich being snagged badly by a bunch of overcovered poor people (along with ignoring the skewing to the rich of the tax code, not to mention the role of rising medical care costs in the spending patterns).

Apple’s Effective Tax Rate: New York Times versus Fox Business

Fox Business is claiming that the New York Times got the story as to how Apple avoids paying taxes in the US wrong:

But using Apple’s corporate accounting profit to arrive at its effective global rate of 9.8% is dubious because profit figures are different numbers versus the taxable income figures companies report to the Internal Revenue Service. A look at Apple’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission shows the more appropriate effective rate for Apple is likely more than double the 9.8% effective rate the Times reported. Apple already reports in its filings that its global effective rate for both 2011 and 2010 is 24%, and its effective U.S. federal rate is likely 20.1%. Moreover, its global effective rate for 2009 was 31.8%.I did look at Apple’s 10K filing for fiscal year ended September 24, 2011 and some of what the New York Times wrote is basically correct:

Apple’s accountants have found legal ways to allocate about 70 percent of its profits overseas, where tax rates are often much lower ... In Apple’s last annual disclosure, the company listed its worldwide taxes — which includes cash taxes paid as well as deferred taxes and other charges — at $8.3 billion, an effective tax rate of almost a quarter of profits … tax experts say that strategies like the Double Irish help explain how Apple has managed to keep its international taxes to 3.2 percent of foreign profits last year, to 2.2 percent in 2010Income before provision for income taxes was $34.2 billion while the tax provision was almost $8.3 billion. So the reported effective tax rate was over 24% not less than 10%. But the New York Times article noted that. So let’s go to the details as reported in Note 5 (Income Taxes), which notes that foreign pretax income was $24 billion with about $10 billion in reported US taxes. In other words, Apple did allocate 70% of its profits overseas. Foreign taxes were only $0.6 billion or 2.5% of its foreign pretax income. So why was its tax provision so high? The Federal portion was almost $6.9 billion due to almost $3 billion in deferred Federal taxes. The one thing that troubled me about the New York Times article was its claim that Apple avoided California taxes with its Nevada operations. This not only ran contrary to my understanding of how California tax law works but seems to be contradicted by the fact that the state tax provision was almost $0.8 billion or just under 8% of US pretax income. Two parables I guess – (a) understanding tax provisions isn’t always easy; and (b) don’t trust everything you read in the news especially if it is from Fox.

Paul Ryan – Imposing Austerity in order to Avoid It?

Paul Ryan’s interview with Jonathan Weisman included a passage that shows how utterly clueless he is noting that the Republican fiscal policy objective is to:

preempt austerity – we want to prevent that bitter kind of European austerity mode which is what we will have if we have a debt crisis.In other words, cut government spending now to avoid fiscal restraint later? Does he not know that we currently suffer from a lack of aggregate demand? We should be avoiding fiscal restraint now but considering long-term measures to reduce government deficits. Then again – the prime minister of the UK seems to be just as clueless as Congressman Ryan. How well is that working out?

Sunday, April 29, 2012

Are the Republicans Denying Gender Pay Disparity?

Meet the Press featured a debate between Rachel Maddow and Alex Castellanos. When Ms. Maddow noted a recent finding by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research noting that women earn 77 cents to every dollar earned by men, Mr. Castellanos first denied there was any disparity and then argued factors such as the choices when make about how much to work or what professions to enter explain all of any alleged difference.

Really? What evidence did Mr. Castellanos offer for this claim? None apparently - even though there has been substantial research on this issue. This 2008 OECD chapter summarizes much of this research:

Regression-based decompositions have been used in the literature to try to identify the sources of wage gaps between men and women. These decompositions allow assessing how much of the gap is explained by observed gender differences in terms of individual productive characteristics, the remaining unexplained portion being ascribed to differences in unobserved characteristics and/or asymmetries in labour demand (see OECD, 2008a). Educational attainment and labour market experience typically explains only a small or even negligible portion of the gender wage gap. By contrast, labour market segmentation by occupation, type of contract, industry as well as firms and establishments typically explain a far larger share (see e.g. Altonji and Blank, 1999; Reilly and Wirjanto, 1999; Datta Gupta and Rothstein, 2005; Heinze and Wolf, 2006). However, evidence based on large-scale matched employer-employee data shows that even taking into account a fine disaggregation of occupations, industries and establishments, more than 50% of the wage gap remains unexplained (e.g. Bayard et al., 2003). More important, the gender distribution of jobs is itself the outcome of the equilibrium in the labour market. It provides therefore some indication of the channels through which a gender wage gap arises, but sheds no light on the ultimate causes of the gap.

Crit Quant

Frank Bruni addresses an issue in his New York Times column this morning that colleges and universities across the country are confronting: how to adapt to a world in which technological skills are in greater demand while hanging on to as much of their traditional mission as possible. Let’s put it starkly: higher ed needs to turn out more engineers and number crunchers, and it also needs to keep the fires (embers?) of critical consciousness burning.

In my state of Washington, and maybe yours, this takes the form of increasing political pressure for universities to crank out “high demand” majors. This doesn’t refer to student demand—quite the opposite—but demand from the state’s largest and most politically connected employers. This includes STEM, of course, but also nursing. (Beleaguered and underpaid nurses abandon their profession en masse each year, and this is seen as a reason to train ever more of them.) But let’s talk about STEM.

The pushback from defenders of the liberal arts is that education is not just about filling job slots, but about citizenship. The future of our country, nay the human race, depends on the cultivation of new generations who can see past the shiny surfaces to the deep questions of life, who are habituated to critique, whose perceptions are heightened by aesthetic acuity, etc. The call for STEM is really an effort to eviscerate society’s main sanctuary for critical consciousness.

I think this is not an either/or question, but both/and. We need to think deeply and also be productive. Critical consciousness has to pay its way. To get from platitude to program, however, we have to consider what this means in practice.

The obvious answer, and the one most of the attention is now focused on, is rebalancing. We need somewhat more STEM students and somewhat less in the other fields. To the extent that there is intellectual fat in a university’s catalog, it can be cut without harm to the liberal arts bone, so to speak. Hire a few more STEM PhD’s a few less of the other sort. Adjust and carry on.

To my way of thinking, this approach evades the real issue. Engineers need to be critical thinkers, and critical thinkers need to be quantitative. Not each and every one (reject corner solutions!), but lots of them. The democratic and transformative agenda of higher education has to pervade its economic agenda, and also, to a large extent, vice versa.

This translates to increased traffic between the technical fields and the rest of the liberal arts. Engineering curricula should include industrial design to develop aesthetic appreciation for objects, along with historical and social approaches to technology to promote a critical, questioning spirit. (Engineers may also benefit personally in their future careers from studying labor history.) Meanwhile, philosophers should be learning game theory and historians more rigorous methods of quantitative data analysis. Ideally these would be bottom-up reforms, arising voluntary, even enthusiastically, from the faculty themselves. In practice, they will have to be elicited and nurtured, with strategic reallocation of funds and pressure on new hiring.

Perhaps this is the easy part. To make it all work there also needs to be a fundamental change in the place of quantitative reasoning in our culture—in the schools, the media and daily life. The faculty and students who, in my dreams, will meld critical thinking and quantitative adeptness will not materialize spontaneously because a new course offering has been inserted into the catalog. Somehow we have to challenge the view that the ability to do math is confined to a small subset of our species, and that it’s OK for the rest to just opt out. Math classes have to do a lot more teaching and a lot less sorting; would we accept writing classes that allowed the great majority of students to come to terms with their inability to write by believing that they don’t have that special writing gene?

But this is another rant for another day.

Friday, April 27, 2012

Income versus Wealth

One way to think about the political economy of macropolicy is to divide people into two camps, those who are motivated primarily by threats to income and those by threats to wealth. (I will emphasize threats rather than enhancements for simplicity, and in recognition of the force of loss aversion.)

Threats to income take the form of unemployment, wage loss and the loss of public benefits (the social wage). The policies attractive to this group are generally Keynesian: looser fiscal and monetary policy, measures to increase wages, and other interventions to prevent the economy from producing below its potential due to insufficient demand.

Threats to wealth take the form of inflation and default. The policies these people are drawn to are what we usually call orthodox: tight monetary policy, restrictions on new borrowing (particularly by the public sector) and hostility to measures that would reduce the profitability seen as underlying asset and credit markets. The latter often comes dressed as labor market flexibility.

Note that I am not passing judgment (here) on what is right or wrong, good or bad, from an economic standpoint. I am only attaching particular policy constellations to particular (perceived) interests. I also recognize potential inconsistencies; in particular, those concerned to preserve the value of their wealth might lean toward Keynes if they fear that insufficient demand will lead to declining profits, lower share prices and higher default rates. (My modeling hypothesis: this effect is nonlinear in the rate of change in the output gap. If the output gap is approximately stable or falling, wealth-holders will put this concern below the others mentioned earlier. If the output gap is rising, perhaps beyond some threshold rate, the Keynesian threat to wealth takes center stage.)

Do these perspectives correspond to class interests? Yes and no. Clearly wealthier individuals are likely to be more concerned with wealth rather than income, and the reverse holds for those with little wealth. Nevertheless, it is not a strict mapping. There are high income individuals, for example in upper-level management positions, whose vulnerabilities arise far more from their future employment prospects than their portfolios. Similarly, many middle class retirees are highly dependent on the performance of their savings. In fact, this last example reminds us that there is a life cycle aspect to this divergence of interests as well as a class aspect, although the class influence is probably larger overall.

How do these perspectives reveal themselves in economic policy discourse? We know about orthodoxy: it defends itself explicitly on the grounds of wealth effects. Inflation is always just around the corner, and any additional public borrowing puts the state on the slippery slope to insolvency. People must learn to live on less and to repay all their debts in full. The one interesting twist is that, recognizing that wealth preservation is not a widespread concern, those arguing for orthodoxy have tried to present inflation as primarily a threat to income: “the cruelest tax of all”. To do this, of course, they have to put aside the identity between incomes and expenditures (as adjusted by the current account), meaning that their appeal is based on sowing confusion. The fact that this particular falsehood cannot be put to rest by rational argument suggests that political economy plays a more powerful role in shaping discourse than economics.

On the Keynesian side, much is made of the threat of demand shortfalls to profits and markets in claims on profits, and arguments are made that concerns regarding inflation and public insolvency are overblown. Perhaps the reason these arguments are only sporadically effective is that they do not address the very different weights wealth-holders place on income versus wealth threats, nor their perhaps justifiable concern (from their perspective) over tail risks.

There is an emotive side to this dispute. Keynesians, by emphasizing the potential, even in the near term, for future wealth production, express optimism—a can-do attitude. Follow the right policies and we can advance together to a higher quality of life. The orthodox, who want to protect the accumulation of past wealth, express a sort of dourness. Adjust to the hard times, tighten your belt, and eventually we will get through this. In pointing to this, I am trying draw out the implications of the difference between the two perspectives in their orientation toward time.

How well does this model capture the current debate in Europe and the US?

ADDENDUM: I left out the confidence argument that is so important to the orthodox side. In public debate, they want to portray threats to wealth as equally threats to those without wealth. The way they do this is to argue that wealth-holders play a decisive role in investment, and investment is the key to protecting incomes. If threats to wealth can be removed, they say, the resulting peace of mind (confidence) will set off an investment boom. The essential role that the confidence trope plays in selling wealth protection to an income-preoccupied public explains why so much stress is placed on a claim that, by its nature, is almost incapable of reasoned support ex ante.

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Europe: Ignorance Does Not Even Remotely Resemble Bliss

The public debate over European austerity, so long overdue, is now breaking out. The baby steps of Hollande in France, the double dip in England, the difficulty in assembling an austerity coalition in the Netherlands and the first big anti-austerity demonstration in the East (Czech Republic) are all signs that fiscal orthodoxy is under siege. The backdrop, of course, is the descent of much of Europe into recession when the recovery from the financial crisis has barely begun. Given that officials have postponed a reckoning with the losses amassed by the banking system, this is a recipe for an even greater disaster.

What stands out at this point is the extraordinary ignorance displayed by the defenders of austerity. Whether this is honest ignorance or the cynical kind is difficult to say, but in either case it should be shown for what it is.

Let’s take two comments culled from this morning’s New York Times coverage. First we hear David Cameron, the British PM, in what has become the mantra of the austerians: “More debt and more spending is what got us into this problem. It can’t be the solution of the problem.”

1. Except for Greece, public sector deficits were modest and generally declining in the runup to 2008. In what sense did public spending provoke the collapse of the global financial sector in the fall of that year?

2. Fiscal deficits ballooned in response to the crisis; they were a symptom rather than a cause.

3. It was actually private debt that got us into this mess. Public debt has expanded to limit defaults and partially take up its role in sustaining spending.

4. Lack of spending is surely the core issue at present. Demand for goods and services is depressed, workers are out of work, and investment is anemic. Borrowing is how spending expands in advance of income. Either the private sector has to take on more debt or it’s the public sector’s job. But the private sector is justifiably deleveraging. Governments that can print money need to take up the slack. When income growth revives, public borrowing can recede.

Not a single word of this quote is defensible. That includes “and” and “the” (both of them).

Now listen to Draghi. Arguing against fiscal stimulus, he says, “If one thinks you can increase demand by increasing deficits, then how come we don’t have higher demand?”

1. Again, the fiscal deficits are a symptom of the slump. We got drastically lower demand, and then we got deficits. Draghi might as well ask, if crutches are so good for getting around, why don’t we see more people on crutches in the Olympics?

2. The austerians are demanding that deficits shrink. This will decrease demand and intensify the slump.

3. The deficits are doing less than they should to stimulate demand because a portion of government spending, especially in places like Ireland and Spain, is going to bail out the financial sector. With no EU-level plan to either bail out or resolve finance, it is left to individual countries to do this. Since Draghi is not doing the job a real central banker should be doing, at least he can stop criticizing those who are trying to do some of it for him.

Just as irrationally, Draghi goes on to say that growth can come only from structural reform that makes economies more efficient. Huh? That’s about the growth of supply, not demand. True, if an individual country gains in efficiency relative to the others, and if its exchange rate doesn’t adjust (perhaps because it has given up its own currency), then, yes, it can boost its demand through an increase in net exports. But this is a zero-sum game overall. Rebalancing is important for averting the structural forces that create unsustainable debts, but that has little to do with aggregate demand across the system.

So what I propose is this: expose the absurdities of austerian arguments every day. Don’t let any of it pass. Let’s get to the point where denying basic economics is like denying climate change, where ordinary people can see that the controversy is an expression of who is paid to say what, not the underlying science.

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Education: Low Interest Student Loans – A Very Small Step

Mitt Romney apparently agrees with President Obama on extending the 3.4% interest rate on student loans, which puts both of them at odds with Republicans in Congress. Of course, we will have to wait and see if Mr. Romney shows any real leadership in helping the President overcome the opposition in Congress from his own party.

I would humbly submit that this is only a very small step in restoring the recent damage to our education system. Our chart shows the decline in real government spending using data from this source (see Table 3.15.6. Real Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment by Function). Phil Oliff and Michael Leachman documented how state and local government support of elementary and high school education has been declining since the recession.

Diane Epstein discussed what the Ryan budget would mean to education spending a month ago. Pell Grants, which already have seen declining values relative to college costs, are slated to be drastically reduced. Head Start funding will also be reduced.

Of course, most of what public commitment to education comes from state and local governments, but the Federal government can reverse these recent cuts with a greater commitment to Federal revenue sharing. And the bonus would be that we might avoid doing further damage to the economic recovery ala austerity. In other words – if Mr. Romney wants to really lead, then he will insist that we reject this Ryan budget.

Keynes was right and the Austerians are wrong

Via Paul Krugman comes a report from Henry Blodget that a few European leaders have finally figured out:

Keynes was right and the Austerians are wrong.

And BBC reports that the UK economy has seen real GDP decline for two consecutive quarters. BBC also notes:

Prime Minister David Cameron said the figures were "very, very disappointing". "I don't seek to excuse them, I don't seek to try to explain them away," he said at Prime Minister's Questions. "There is no complacency at all in this government in dealing with what is a very tough situation, which frankly has just got tougher." He said it was "painstaking, difficult" work, but the government would stick with its plans and do "everything we can" to generate growth.Does he mean sticking to austerity, which likely caused the economic downturn?

The Precautionary Principle and the Iraqi WMD Test

My emeritus colleague, John Perkins, asks a deep question about proposed justifications for a precautionary principle: would they, in early 2003, have provided a basis for the US invasion of Iraq despite, or even because of, uncertainty about the existence of Iraqi weapons of mass destruction? The stylized decision situation is this: the US has suspicions that horrible chemical or biological weapons are being stockpiled in Iraq, but there is no firm evidence. Indeed, the likelihood of WMD’s is small, but the negative consequences if they actually exist are severe. Suppose further that decision-makers are honest (this is a purely hypothetical test) and want to act rationally so as to minimize the harm of either launching or not launching military action. In other words, this is a make-believe scenario, but one that nevertheless captures an important aspect of the meaning of precaution: if being precautionary in such a situation makes you more likely to want to invade Iraq, you have a problem.

So is there a version of the precautionary principle that passes this test? Intergenerational equity arguments (irreversibilities justify low or zero discount rates) are at best a wash, since the costs of under- or overestimating the likelihood of WMD’s have approximately the same time profile. (The main problem with intergenerational equity is that, while it is a fine concept, it has little relevance to most situations that might require precaution; precaution is about coping with uncertainty, not valuing immediacy versus delay.) Fat tail aversion à la Weitzman would seem to fail the test, since it would place greater value on insuring against catastrophic WMD risk. According to this principle, it’s better to accept the certain devil we do know (invasion) than run the risk of the less likely but even worse devil we don’t. You could argue for a different type of precaution: don’t mess with nature. This would avoid WMD dilemmas by defining precaution as being about only environmental questions, but at the cost of being either grossly impractical or incoherent. Example: agriculture, even the most organic kind, is absolutely messing with nature, as are many of the other essential practices of the human race. Green-is-good is an attitude, not a rational basis for a decision principle.

I think my version of precaution does pass the test. To recap (OK, not “re” for most readers), I propose that metadata—the history of how we have learned in the past—is relevant to evaluating our ignorance in the present. If a company had a record of underperforming its earnings target quarter after quarter, you would take this into account even if you had no current information regarding the likelihood of its meeting its next target. Similarly, what distinguishes the emergence of ecological understanding over the past century or so is that we systematically discover that species, including our own, are more interdependent than we thought, and more sensitive to alterations in their natural environment at lower exposure thresholds. It is rational to expect that the larger part of our current uncertainty regarding environmental impacts will resolve itself in similar ways in the future; hence precaution.

Here is why I think it passes Perkins’ test. On the one hand, there has been a long series of manipulated intelligence reports used to justify policies favored by those in power in Washington; foreign threats usually turn out to be less threatening than initially reported. (Intelligence pertaining to Japan pre-1941 might be an exception, maybe.) On the other, invasions of foreign countries have typically turned out worse than expected: more resistance, more repression in response to resistance, more cruelty, more overall economic and human cost. On both counts the metadata should be incorporated into the decision process, and both counsel precaution as I understand it.

My golden rule of precaution: make the decision today that, based on everything you know up to this point, you will be most likely to have wished you had made in the future, when you will have more information. Assess the likely bias of your ignorance.

Inequality: Finance and Geography

I’ve just finished watching Jamie Galbraith’s INET talk on inequality (thanks, Yves) and was struck by his geographic discussion toward the end. Most of the increase in US inequality in the last decade or two has been concentrated in just a handful of counties, particularly Manhattan, San Francisco, King (Seattle) and a few others.

Let’s suppose the explosion of high incomes in the financial sector accounts for about a fourth of the increased share claimed by the top 1%. (Does anyone out there have a real number for this?) Given geographic concentration, we should look also at the services consumed by the financial elite. A rough law has it that the earnings of a service provider are proportional to the income of his or her clients. A dog walker to the rich makes more than a preschool teacher in a low-income neighborhood. We can therefore propose a sort of inequality multiplier associated with the initial bounty bestowed on those in finance: much more prosperous decorators, physicians, restauranteurs, etc. These spillovers would be concentrated in close geographic proximity to the location of financial centers. The point is that there are both direct and indirect effects of finance’s grip on profits, much of which would not be captured by existing empirical methods.

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Could a Strong Union Movement Save Social Security?

Pear, Robert. 2012. "Social Security’s Financial Health Worsens." New York Times (24 April): p. A 13.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/24/us/politics/financial-outlook-dims-for-social-security.html?hp

"The Obama administration reported a significant deterioration in the financial outlook for Social Security on Monday, while stating that the financial condition of Medicare was stable but still unsustainable."

"The Social Security trust fund will be exhausted in 2033, three years sooner than projected last year, the administration said."

"In explaining changes in their Social Security projections, the trustees cited slower growth in average earnings of workers and the persistence of unemployment in the slow recovery from the recession. They lowered their projection of average real earnings in the future, primarily because of a surge in energy prices and “slower assumed growth in average hours worked per week after the economy has recovered.”

Let's see if we can get this straight. For 40 years wages have gotten hammered by the "job creators". People become increasingly reliant on Social Security, but the system is in trouble because people do not earn enough to get enough taxes taken away to cover social security. The obvious answer is to destroy social security.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/24/us/politics/financial-outlook-dims-for-social-security.html?hp

"The Obama administration reported a significant deterioration in the financial outlook for Social Security on Monday, while stating that the financial condition of Medicare was stable but still unsustainable."

"The Social Security trust fund will be exhausted in 2033, three years sooner than projected last year, the administration said."

"In explaining changes in their Social Security projections, the trustees cited slower growth in average earnings of workers and the persistence of unemployment in the slow recovery from the recession. They lowered their projection of average real earnings in the future, primarily because of a surge in energy prices and “slower assumed growth in average hours worked per week after the economy has recovered.”

Let's see if we can get this straight. For 40 years wages have gotten hammered by the "job creators". People become increasingly reliant on Social Security, but the system is in trouble because people do not earn enough to get enough taxes taken away to cover social security. The obvious answer is to destroy social security.

The Not-So-Secret Weapon of the Campaign to Destroy Social Security: Cynicism

First, read these two articles, one from the Harvard School of Journalism, the other from the New York Times, back to back. A match made in heaven, no?

Now that you’ve done your homework, here is my take. For the past thirty years we have seen repeated campaigns to eviscerate Social Security—to privatize it, siphon off its finances, drain it of its essential social insurance character. These have failed, not because of the brilliance or commitment of its defenders, but simply because it fulfills a vital social function and is wildly popular. Even those who, in their heart of hearts, want to crush it to bits, claim to be in favor of “saving” it. So what’s the strategy of the anti-SS minions?

Cynicism. Convince younger voters, whose benefits are still decades away, that the program is dying a slow but certain death, and that politicians are too myopic or pandering or just stupid to do anything about it. From time to time I poll my students, and by a big majority they always tell me that SS will not be around to support them in their retirement. (Not that this has provoked a big Feldsteinesque spike in their personal savings....) As this mindset takes hold, it becomes easier to simply tune out the debate over SS. After all, it’s not like it’s actually going to be there when I’m old, no matter what they say, right? At some point, it goes from being a third rail to a footnote to just background noise, to mangle a bunch of metaphors.

What I’d like to see are news stories that say something like, “Social Security has had its ups and downs, but it’s in better financial shape now than it was a generation ago, and unless its enemies prevail, it will be there for you when you need it.”

Monday, April 23, 2012

Pareto's Law: Understanding Inequality

Economists, always intent on making their work into a science, like to transform their ideas into a "scientific" law. Accordingly, the Fascist Italian senator, Vilfredo Pareto is credited with discovering Pareto's Law, which explains why inequality is a natural outcome. Pareto suggested that 20% of causes create 80% of effects. He argued that this law explains why 20% of the Italian population owned 80% of the wealth. Sadly, the U.S. experience calls Pareto's data into question, but then, those lazy Southern Europeans wallow in socialism.

There is a second Pareto Law, which offers a more accurate explanation inequality. In his Manual of Political Economy, he explained:

"In all periods of the history of our country we find facts similar to the practices we have just pointed out, permitting certain persons to use stratagems to appropriate to themselves the goods of others; hence we can assert, as a uniformity revealed by history, that the efforts of men are utilized in two different ways: they are directed to the production or transformation of economic goods, or else to appropriation of goods produced by others. War, especially in ancient times, has enabled a strong nation to appropriate the goods of a weak one; within a given nation, it is by means of laws and, from time to time, revolutions, that the strong still despoil the weak."

Pareto, Wilfredo. 1906. Manual of Political Economy, Ann Schweir, tr. (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1971): p. 341.

The final phrase about the strong despoiling the weak offers an excellent insight into the way that capitalist countries, led by the United States have been repealing Pareto's first law.

There is a second Pareto Law, which offers a more accurate explanation inequality. In his Manual of Political Economy, he explained:

"In all periods of the history of our country we find facts similar to the practices we have just pointed out, permitting certain persons to use stratagems to appropriate to themselves the goods of others; hence we can assert, as a uniformity revealed by history, that the efforts of men are utilized in two different ways: they are directed to the production or transformation of economic goods, or else to appropriation of goods produced by others. War, especially in ancient times, has enabled a strong nation to appropriate the goods of a weak one; within a given nation, it is by means of laws and, from time to time, revolutions, that the strong still despoil the weak."

Pareto, Wilfredo. 1906. Manual of Political Economy, Ann Schweir, tr. (New York: Augustus M. Kelley, 1971): p. 341.

The final phrase about the strong despoiling the weak offers an excellent insight into the way that capitalist countries, led by the United States have been repealing Pareto's first law.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)