That seems to be the message of this morning’s New York Times article about Portugal’s political crisis. The problem, if you want to call it that, is that the governing conservatives came up short in the last election. Three parties of the left—the Socialists, the Communists and the Left Bloc—between them got a majority of the seats in parliament. The president, Cavaco Silva, also a conservative, has turned to Passos Coelho, the head of the conservative alliance, to form a government, but the left deputies have vowed to deliver a vote of no confidence this coming week.

Now, in a normal democratic country people would say, “It looks like the voters have shifted to the left and rejected austerity. The new government will reflect that.” But we are talking about the Eurozone, where such sentiments are viewed as subversive—not only by the eurocrats but also the media, including the Times.

So we are treated in this article to the notion that austerity policies “are credited with arresting Portugal’s economic slide” and that the country is now in the “early stages of a recovery” which is threatened by the “uncertainty” caused by the latest election. The country’s “structural reforms” are at risk, and Portugal now “hangs by a thread”.

The article goes so far as to say

If the Parliament rejects the government’s economic program on Tuesday, it will leave Mr. Cavaco Silva with a hard choice.

He could either allow the left to form a government that promises to unwind part of Portugal’s austerity program, or he could leave Mr. Passos Coelho in place as what promises to be an ineffective, caretaker prime minister until new elections can be held.

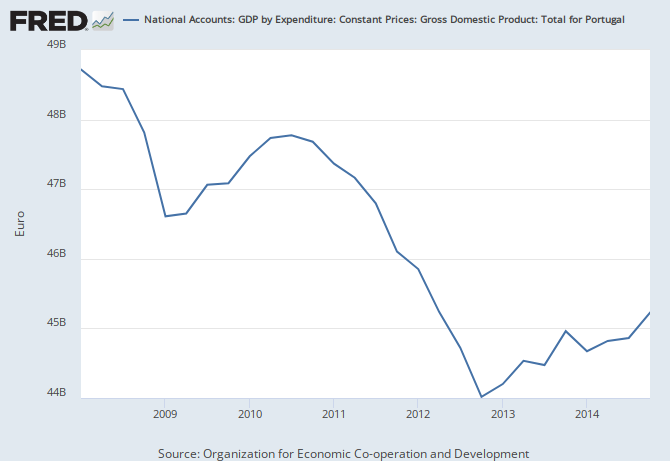

Either outcome seems destined to leave the country in a prolonged crisis....It’s time for a little reality check. Here is Portugal’s real GDP from the onset of the crisis in 2008 to the most recent statistics.

And here is the unemployment rate:

What's that about a "prolonged crisis"? Portugal’s economy is still well below where it was seven years ago, and unemployment continues to be an immense problem. And all of this is unnecessary. Portugal did not suffer some mysterious disappearance of productive assets or skills or natural resources; this is a predictable result of policies that deliberately seek to suppress output and employment. That’s what austerity means.

If there is a criticism of the political rebellion in Portugal, it is that it has been so long in coming. We are now at a moment, however, when democracy and economic sanity have converged. If there’s a crisis, its source is not Portugal but the dictates of the eurocrats. If they are looking for stories about how hard it is to extricate yourself from poor choices, the Times could send its reporters to Brussels and Frankfurt, not Lisbon.

1 comment:

What is the solution? Public banks? Local currency? Debt-relief gardens? Home-made houses? A minimum universal income?

Post a Comment