Yesterday I was asked to write a comment on the debate over initiative I-732 in Washington State which would establish a revenue-neutral carbon tax, and I wrote several paragraphs. Today, after sleeping on it, I realize there is a simple point to be made.

Here’s the background: The Washington initiative is loosely modeled on British Columbia’s carbon tax. It would cover about 3/4 of the economy, taxing carbon at $25/ton. Revenues would be offset by eliminating the main business tax, shaving the state sales tax by a point, and increasing low income tax rebates. A group, Carbon Washington, was formed to promote it. Meanwhile, another group, the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy, bringing together unions, social justice activists and more militant environmentalists, has publicly opposed the initiative. They demand that revenues be funneled into social service programs and public investment. The rhetoric has been heated; I attended a talk the other day in which supporters of I-732 were described as racists.

I have serious problems with the Alliance position, but I’ll put that aside for now. Let’s talk about this “revenue neutral” thing. Why would someone want a carbon tax to be revenue neutral, especially in a state with serious fiscal constraints like Washington? I can think of two reasons. First, it telegraphs to conservatives that there is nothing “big government” about the proposal: you can vote for the initiative while swearing on a stack of Road to Serfdom’s. Second, it’s what results when you rebate the money. The publicity of Carbon Washington has trumpeted both of these.

The first argument is a loser. (1) The number of conservatives who believe climate change is a serious problem that requires government action but will only support a proposal if it leaves the size of government precisely unchanged is vanishingly small. This is a political concession without an upside. (2) Meanwhile, by catering to the small government crowd, Carbon Washington has deeply alienated almost the entire left side of the political spectrum—the natural base for a vibrant climate movement. Using carbon money to eliminate a business tax doesn’t help matters, and the formula used for tax offsets opens the door to the possibility that the system will be revenue negative in some years.

The second argument gets it backward. It’s true that rebating the carbon money will result in revenue neutrality (or something close to it), but it’s the rebate, not the neutrality, that matters. Putting a price on carbon, whether through taxes or auctioned permits, transfers money from the pockets of consumers to the government. This is regressive, since it’s effectively a sales tax, one that low income people can hardly avoid. But rebating the money is a second transfer, from the government back to the people. The point of a well-designed rebate, like an equal per capita dividend, is that the combined system with both transfers is progressive, contributing to greater equality at a time when equality is in very short supply. From a political perspective, you want to be able to argue this. Revenue neutrality is only a means toward this end; why would you make that your selling point? Lots of government handout schemes could be revenue neutral, but what people presumably care about is whether the overall revenue system is fair.

Conclusion: drop this revenue neutrality nonsense. Propose carbon pricing systems that promote equality. Don’t take the side of the ideological enemies of public action. Return carbon money for social justice, not because there is some intrinsic value in keeping revenues just where they are.

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Friday, April 29, 2016

Carbon Politics

I’ve always appreciated David Roberts’ voice in debates about climate policy. He reads widely, looks for the strong points of arguments he otherwise disagrees with, and is open to changing his mind. Even now, when I think he’s been substantially captured by a particularly blinkered stream within the climate change policy world, he’s still worth looking at. Alas, however, his drift toward the Breakthrough Institute view of things is nearly complete.

It would take a book or more to explain why it won’t be possible to simply regulate, subsidize and innovate our way to climate stability. (I’m writing it now in fact.) Let’s skip over all that stuff for now. Here I’d like to say a few words about the politics of climate policy.

Begin with DR’s position in a nutshell: Climate policy is constrained by public acceptance as revealed by polling and other empirical indicators. The public will not support a price on carbon sufficient to achieve meaningful emissions reductions, but it will accept regulations such as fuel economy mandates and shutting down coal plants that are equivalent in their effects to a much stiffer carbon price. Public opinion is even more of a constraint given the expectation that the fossil fuel industry will strenuously oppose any serious policy initiative at all: you need a lot of political approval to counterbalance them. To the extent there is a political upside to carbon pricing it comes from the additional revenues it generates, which can be earmarked for popular spending programs on energy R&D and infrastructure. These have the potential to create their own constituency, which will provide a political base for further climate action in the long run.

Full disclosure: he makes his case partly in response to a posting of short briefing papers by the Scholars Strategy Network (SSN), one of which is mine. You may discount my reactions accordingly.

Anyway, I think there are two big holes in DR’s critique. The first is that he doesn’t measure policy against its purpose. If the goal is climate stabilization—and what else would it be?—the benchmark is the IPCC’s carbon budget for a 2/3 chance of keeping global temperature increases to 2º C or less. That translates to roughly a 4% decline in global carbon emissions every year from now to the complete phaseout of fossil fuels. (Delay makes the job harder, of course.) For political and equity reasons, richer countries will need to cut even more, and the US, with its outsized per capita emissions, will need to cut more than that: an annual 8% cut is in the ballpark. Now, I can hear DR’s voice in my ear. You’re completely nuts. This is so far beyond the bounds of political feasibility it’s a form of mental illness, not policy analysis. I’d agree, except that the numbers are not a matter of choice—they’re dictated by the physics, chemistry and biology of the problem and the laws of arithmetic. We’re a lot more likely to find unanticipated flexibility in politics than in the science of climate sensitivity. From where I sit, DR’s position is the one that has issues with the reality principle.

That brings us to the second hole, the political system itself and its implications for what kinds of policies are feasible. The implicit assumption behind DR’s piece is that we live in a democratic society where public opinion determines political outcomes: the more support there is for a policy, the more likely it is to be adopted. Visually, he has in mind something like this:

Public support, as measured by polling, is on the horizontal axis; high carbon prices with revenue rebates are on the left with small minorities backing them, while low prices coupled with spending on green energy get majority approval. The prospects for being adopted are represented by the vertical axis, and the upward-sloping line tells us that the more support a policy has, the better its chances of being enacted.

Would that it were so.

Now here instead are three diagrams from the groundbreaking study by Gilens and Page based on a database of 1779 policy initiatives they have assembled and analyzed. The first is the relationship between public support at the median income level and the probability of adoption—flatland.

For the vast majority of the citizenry, it doesn’t matter what they think. Of course, political popularity can make or break the careers of politicians, and that’s not a trivial effect, but the record of policy adoption moves independently from the electoral ups and downs of parties and politicians. There is no democratic machinery in the US (or I suspect other large, wealthy countries) that converts the popularity of a proposal into prospects for enactment.

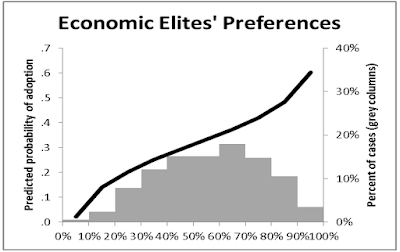

The second diagram illustrates what democracy looks like, but it applies only to the preferences of voters at the 90th percentile, which Gilens and Page take as representative of “elites”. Their preferences do get translated into outcomes.

The third is interesting; it represents the relationship between political mobilization around an issue, as reflected in the formation of pressure groups and their lobbying and similar activities, and the probability that the issue will be decided their way.

Collective action works! The problem is that mobilization requires resources, and resources are concentrated in a few hands. But not always: Gilens and Page find that when bottom-up issue groups come together they can be just as effective as the top-down variety.

What does this all mean for climate policy? First, that the absence of widespread public support for various policy initiatives is not a constraint, just as its presence would not be a basis for success. (I suspect that public support for a policy tends to increase after its adoption, in a sense providing democratic justification ex post, but I don’t know of any empirical evidence on this one way or the other.) By comparison, the move to privatize public education has gained considerable ground in the US without any indication of broad public support. Elite preferences really do matter more.

Second, what really matters is the development of a dedicated mass movement for serious climate policy. We can see it beginning to come together, but it still has a long way to go. I think Theda Skocpol nailed it in her meticulous analysis of the failure of cap-and-trade in 2009: opinion polls, like votes in Congress, is more an effect than a cause of political action, and to get the job done that action needs to maximize citizen mobilization. This model is in the background of my own paper on the SSN website, which is about overcoming the disagreement over the use of carbon revenues that currently impedes the development of a unified movement in Washington State.

In the grand scheme of things, DR occupies one end of the political optimism spectrum, where the existing political framework sets unbudgeable limits to what can be accomplished, a position I’ve referred to earlier as the politics of futility. The other end is the pure willfulness of some portions of the left, for whom, if policies fall short, it can only be due to not enough of us wanting them badly enough—a shortfall of spirit. In between is a large realm of empirically guided, pragmatic radicalism, keeping one eye on the world as it is today and the other on the prize. I think DR used to be in this space, and he’s welcome back whenever he decides to rejoin it.

It would take a book or more to explain why it won’t be possible to simply regulate, subsidize and innovate our way to climate stability. (I’m writing it now in fact.) Let’s skip over all that stuff for now. Here I’d like to say a few words about the politics of climate policy.

Begin with DR’s position in a nutshell: Climate policy is constrained by public acceptance as revealed by polling and other empirical indicators. The public will not support a price on carbon sufficient to achieve meaningful emissions reductions, but it will accept regulations such as fuel economy mandates and shutting down coal plants that are equivalent in their effects to a much stiffer carbon price. Public opinion is even more of a constraint given the expectation that the fossil fuel industry will strenuously oppose any serious policy initiative at all: you need a lot of political approval to counterbalance them. To the extent there is a political upside to carbon pricing it comes from the additional revenues it generates, which can be earmarked for popular spending programs on energy R&D and infrastructure. These have the potential to create their own constituency, which will provide a political base for further climate action in the long run.

Full disclosure: he makes his case partly in response to a posting of short briefing papers by the Scholars Strategy Network (SSN), one of which is mine. You may discount my reactions accordingly.

Anyway, I think there are two big holes in DR’s critique. The first is that he doesn’t measure policy against its purpose. If the goal is climate stabilization—and what else would it be?—the benchmark is the IPCC’s carbon budget for a 2/3 chance of keeping global temperature increases to 2º C or less. That translates to roughly a 4% decline in global carbon emissions every year from now to the complete phaseout of fossil fuels. (Delay makes the job harder, of course.) For political and equity reasons, richer countries will need to cut even more, and the US, with its outsized per capita emissions, will need to cut more than that: an annual 8% cut is in the ballpark. Now, I can hear DR’s voice in my ear. You’re completely nuts. This is so far beyond the bounds of political feasibility it’s a form of mental illness, not policy analysis. I’d agree, except that the numbers are not a matter of choice—they’re dictated by the physics, chemistry and biology of the problem and the laws of arithmetic. We’re a lot more likely to find unanticipated flexibility in politics than in the science of climate sensitivity. From where I sit, DR’s position is the one that has issues with the reality principle.

That brings us to the second hole, the political system itself and its implications for what kinds of policies are feasible. The implicit assumption behind DR’s piece is that we live in a democratic society where public opinion determines political outcomes: the more support there is for a policy, the more likely it is to be adopted. Visually, he has in mind something like this:

Public support, as measured by polling, is on the horizontal axis; high carbon prices with revenue rebates are on the left with small minorities backing them, while low prices coupled with spending on green energy get majority approval. The prospects for being adopted are represented by the vertical axis, and the upward-sloping line tells us that the more support a policy has, the better its chances of being enacted.

Would that it were so.

Now here instead are three diagrams from the groundbreaking study by Gilens and Page based on a database of 1779 policy initiatives they have assembled and analyzed. The first is the relationship between public support at the median income level and the probability of adoption—flatland.

For the vast majority of the citizenry, it doesn’t matter what they think. Of course, political popularity can make or break the careers of politicians, and that’s not a trivial effect, but the record of policy adoption moves independently from the electoral ups and downs of parties and politicians. There is no democratic machinery in the US (or I suspect other large, wealthy countries) that converts the popularity of a proposal into prospects for enactment.

The second diagram illustrates what democracy looks like, but it applies only to the preferences of voters at the 90th percentile, which Gilens and Page take as representative of “elites”. Their preferences do get translated into outcomes.

The third is interesting; it represents the relationship between political mobilization around an issue, as reflected in the formation of pressure groups and their lobbying and similar activities, and the probability that the issue will be decided their way.

Collective action works! The problem is that mobilization requires resources, and resources are concentrated in a few hands. But not always: Gilens and Page find that when bottom-up issue groups come together they can be just as effective as the top-down variety.

What does this all mean for climate policy? First, that the absence of widespread public support for various policy initiatives is not a constraint, just as its presence would not be a basis for success. (I suspect that public support for a policy tends to increase after its adoption, in a sense providing democratic justification ex post, but I don’t know of any empirical evidence on this one way or the other.) By comparison, the move to privatize public education has gained considerable ground in the US without any indication of broad public support. Elite preferences really do matter more.

Second, what really matters is the development of a dedicated mass movement for serious climate policy. We can see it beginning to come together, but it still has a long way to go. I think Theda Skocpol nailed it in her meticulous analysis of the failure of cap-and-trade in 2009: opinion polls, like votes in Congress, is more an effect than a cause of political action, and to get the job done that action needs to maximize citizen mobilization. This model is in the background of my own paper on the SSN website, which is about overcoming the disagreement over the use of carbon revenues that currently impedes the development of a unified movement in Washington State.

In the grand scheme of things, DR occupies one end of the political optimism spectrum, where the existing political framework sets unbudgeable limits to what can be accomplished, a position I’ve referred to earlier as the politics of futility. The other end is the pure willfulness of some portions of the left, for whom, if policies fall short, it can only be due to not enough of us wanting them badly enough—a shortfall of spirit. In between is a large realm of empirically guided, pragmatic radicalism, keeping one eye on the world as it is today and the other on the prize. I think DR used to be in this space, and he’s welcome back whenever he decides to rejoin it.

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

Incidence of the Soda Tax

Paul Krugman comments on an interesting debate between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton:

So Sanders and Clinton are arguing about soda taxes — Clinton for, as a way to raise money for good stuff while discouraging self-destructive behavior, Sanders against, because regressive.Let’s concede the presumption that low income households spend a greater share of their limited income on Coca Cola than high income households but take a look at the incidence of a tax:

A tax incidence is an economic term for the division of a tax burden between buyers and sellers. Tax incidence is related to the price elasticity of supply and demand. When supply is more elastic than demand, the tax burden falls on the buyers. If demand is more elastic than supply, producers will bear the cost of the tax.Of course this is the standard competitive model. Let’s assume such a model with a horizontal supply where the marginal cost of making and selling a bottle of Coke is $1. Imposing a tax equal to $0.20 per bottle will raise the price of a bottle of Coke to $1.20 a bottle with the full incidence on consumers. One could argue, however, that Coca Cola is closer to a monopoly. Let’s imagine in your town that the demand for soda is given by P = a – b(Q), where P = price, Q = quantity, a = 3, and b = 0.01. The competitive market solution puts the price before new tax at $1 and Q = 200. But if Coca Cola has a monopoly, then it raises the price to $2 by reducing Q to 100. In this monopoly model, a $0.20 tax raises the price from $2 to $2.10. In other words, part of the incidence of the soda tax would be borne out of profits rather than simply from consumers. Of course, I’m assuming a simple monopoly model with a linear demand curve. I’ll leave this question of who bears the actual incidence of a soda tax for the capable economists on either Team Bernie or Team Hillary.

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

Could A Higher Minimum Wage Increase Employment?

One of the debates among the Democrats is how much to raise the minimum wage. The President wants it near $10 an hour, Mrs. Clinton is talking about $12, while Bernie Sanders and others are saying $15. Of course Team Republican freaks out as to how any increase in this wage floor will cause job losses. As David Henderson noted:

As is well known in economics, a skillfully set minimum wage, in the presence of monopsony in the labor market, can actually increase employment…To say that a firm has monopsony power is to say that the supply curve of labor to the firm is upward-sloping. That is, the firm is not a price-taker in the labor market. So when the firm that employs n workers and pays Wn per worker wants to hire one additional worker, it needs to pay more to each worker than it paid when it hired n workers. Call this new wage Wn + x. But that means that the cost of hiring that n + 1st worker is not the wage, Wn + x, that the firm pays the worker: it's that wage, Wn + x, plus x times n. The reason: it pays all the other n workers that increment, x, also. Because the firm recognizes this, it hires up to the point where the value of marginal product = Wn + x + x*n. Now, if the government skillfully sets a minimum wage a little above Wn + x, the firm knows that it can't reduce the wage by hiring fewer people and also knows that it won't raise the wage by hiring a few more people and so it hires more people. The main reason people started talking about monopsony in the context of the minimum wage in the 1990s was the study, and later the book, by David Card and Alan Krueger.Let’s flesh this out in a hypothetical town called Old Haven – which is loosely based on the one company town where Yale dominates the labor market for certain types of labor. Let’s assume that Old Haven used to have lots of law firms hiring secretaries with the labor demand curve (D) given by c – d(Wage) and the labor supply curve (S) given by a + b(Wage) with a = negative 8000, b = 84,000, c = 1,960,000, and d = 80,000. I have pegged my example such that a perfectly competitive market would have generated a wage rate = $12/hour and employment = 1 million secretaries. One day Old Haven woke up to the horrors of Cellini & Barnes, which basically merged all of its law firms into a monopsonist that wanted to lower the wage rate to $7.94 an hour but realized it had to obey the local minimum wage of $8 an hour. Cellini & Barnes ends up hiring only 664,000 secretaries. The good news is that the local citizens rebelled and decided to pass a minimum wage of $12 an hour, which induced Cellini & Barnes to hire 1 million secretaries. I wonder if such a development would ever lead Mark Perry to write:

Recent evidence from Old Haven’s experiment of raising its minimum wage by 50% has shown that such changes in certain situations can lead to a 50% increase in employment.Of course, a later proposal might be put on the ballot to raise this minimum wage even further at which point the Wall Street Journal starts going really crazy. Speaking of going crazy - Ed Resner (former McDonald’s CEO) writes:

I can assure you that a $15 minimum wage won’t spell the end of the brand. However it will mean wiping out thousands of entry-level opportunities for people without many other options. The $15 minimum wage demand, which translates to $30,000 a year for a full-time employee, is built upon a fundamental misunderstanding of a restaurant business such as McDonald’s. “They’re making millions while millions can’t pay their bills,” argue the union groups, suggesting there’s plenty of profit left over in corporate coffers to fund a massive pay increase at the bottom. In truth, nearly 90% of McDonald’s locations are independently-owned by franchisees who aren’t making “millions” in profit. Rather, they keep roughly six cents of each sales dollar after paying for food, staff costs, rent and other expenses. Let’s do the math: A typical franchisee sells about $2.6 million worth of burgers, fries, shakes and Happy Meals each year, leaving them with $156,000 in profit. If that franchisee has 15 part-time employees on staff earning minimum wage, a $15 hourly pay requirement eats up three-quarters of their profitability. (In reality, the costs will be much higher, as the company will have to fund raises further up the pay scale.) For some locations, a $15 minimum wage wipes out their entire profit. Recouping those costs isn’t as simple as raising prices. If it were easy to add big price increases to a meal, it would have already been done without a wage hike to trigger it. In the real world, our industry customers are notoriously sensitive to price increasesArcos Dorados Holdings is the largest franchisee and is publicly traded. While its operating margin is around 6%, it also pays royalties equal to 5% of sales to McDonald’s. It reports payroll expenses equal to about 20% of sales. If it were true that there was no effect on menu prices, then a 50% increase in payroll costs would leave these joint profits at around 1% of sales. But here is the problem with this assumption – the minimum wage increase would apply to the competitors of McDonald’s as well. Higher prices for Whoppers will provide room for a modest price increase in Big Macs.

Monday, April 25, 2016

Is the Road to Hell Paved with Pareto Improvements?

In a large multiplayer prisoner’s dilemma, any change in any one individual’s strategy doesn’t affect anyone else, so a player can know that defection will be a Pareto improvement. We might say that the problem of social evil is that the road to hell is paved with Pareto improvements. -- Ted Poston, “Social Evil,” Oxford Studies in Philosophy of Religion, Volume 5Poston's "social evil" is what previous authors have called a social trap or, more famously, the tragedy of the commons.

A Pareto improvement is a change that makes at least one person better off without making anyone worse off. According to the standard fable, voluntary exchange results in a Pareto improvement because each party in the exchange gets something they wanted more than what they gave up for it.

A prisoner's dilemma involves a situation where the individual payoff to each player for defection is better, regardless of whether the other player defects or co-operates but the collective payoff is maximized when both players co-operate.

In a large multiplayer prisoner's dilemma game, defection by some players may have no effect on the other players' outcomes, while defection by a large number of players may have catastrophic effects after some vaguely defined tipping point has been reached. Within limits, defections thus appear to result in a Pareto improvement, where some players are made better off and no one is made worse off.

In Fights, Games and Debates, Anatol Rapoport presented a production and exchange model that deserves to be much better known. It is a very elementary model and thus, as Rapoport warns repeatedly, the results should not be taken as a faithful depiction of what is likely to happen in reality. However, it offers some critical insights into "common sense" assumptions and specifically into the idea of Pareto improvement, which is also based on extreme simplification.

Rapoport's production and exchange "society" consists of two people who each produce goods and exchange with each other a uniform, fixed ratio of their products. The individuals derive utility from the goods they produce and, presumably, can increase their utility by exchanging some of the goods they produce for the different goods their counterpart produces.

Effort to produce those goods, however, is a disutility. The utility from goods increases logarithmically as the quantity of goods increases but the disutility of effort increases in proportion to the amount of effort expended.

Agents in this model can only change their utility by increasing or decreasing their own effort and output. Thus, plotted on a graph, X can only move along the x-axis and Y can only move along the y-axis. Under the stipulated conditions, a stable equilibrium can only be achieved when the utility of the proportion retained by each producer is larger than the disutility of effort.That is to say, the proportion retained cannot be too small and the disutility of effort cannot be too large.

In the absence of a stable balance, any relaxation of effort by one of the agents will lead to parasitism by that agent as the other will immediately compensate by increasing effort, the first agent will slack off more to compensate for the increased effort of the other -- and so on.

But even in the presence of a stable equilibrium, the total utility of the two agents, at the balance point, will be less than the total would be without exchange, as long as their production/effort decisions are guided solely by their own utility rather than by some agreement about how to link their production effort to achieve a "social optimum." This outcome is contrary to the "common sense" interpretations of Pareto improvement and Pareto optimality. As Rapoport cites his mentor, Nicolas Rashevsky, it turns out that:

The only 'ethics' which leads to the attainment of maximum joint utility in the model of society we have considered is the 'egalitarian ethic,' in which the concern for self and for other are of equal weight.It would be easy to dismiss Rapoport's conclusion as pertaining only to very restrictive premises. This is a point that Rapoport reiterates throughout his exposition. But the objection applies equally to Pareto's model.

Vilfredo Pareto is not readily perceived as a proponent of the egalitarian ethic. In his model, though, Rapoport unpacked a tacit premise of Pareto that rational agents would act "as if" guided by some unacknowledged intuition of linkage -- one might even call this invisible intuition "moral sentiments."

Furthermore, the restrictiveness of Rapoport's assumptions may not be as unrealistic as it seems at first. The fixed ratios of exchange can be relaxed to merely widespread similarities in the ratios of exchange. The specification for a stable equilibrium that the proportion of an individual's product exchanged does not exceed the proportion retained can be rationalized by the fact that there is a roughly equal number of hours of unpaid household work performed in the world as there are waged hours of labor. All this is before we move on to the issue of "multiplayer games" -- of a society in which individual actions that ostensively do no harm may accumulate into "social evil."

In Beyond the Invisible Hand, Kaushik Basu examined the issue of outlawing yellow dog contracts, as the Norris-LaGuardia Act did in 1932:

It could he claimed that if one worker prefers to give up the right to join trade unions in order to get a certain job that demands this of workers, then this may be a Pareto improvement. But if such yellow dog contracts are made legal, then lots of firms will offer these contracts, and the terms for jobs without a yellow dog clause may deteriorate so much that those who are strongly averse to giving up the right to join unions will he worse off in this world.Basu proceeds to consider labor standards in cases in which there are multiple equilibria. He asks, "Should the law be used to set a limit on the number of hours that a worker is allowed to work?" His answer -- backed by reference to supporting empirical studies -- would earn the scorn of economists who fancy a lump of labor behind every proposal for shorter hours:

A statutory limit on work hours can, by limiting the supply of labor, push up the hourly wage rate, and it is possible that at this higher wage rate people would not want to work that many hours. In other words, the labor market may have two or more equilibria, in which case banning the long work-hours equilibrium is fully compatible with a commitment to the Pareto principle.Unpacking Pareto optimality and Pareto improvement, as Rapoport's model of production and exchange does, undermines the premise of the road to hell being paved with Pareto improvements. If there is indeed a tacit moral sentiment, a secret egalitarian ethics at the heart of the Paretian idea, then any violation of trust will impose a loss of utility on everyone else -- perhaps even on the violator. Those individuals gains through defecting were only "improvements" assuming an ethical vacuum. What is the point of building a road to a hell when one is already there? In an ethical world, violations of trust are losses of utility.

UPDATE: I have made a pdf copy of the section on the production and exchange model in Rapoport's Fights, Games and Debates. Below is the equation for the utilities of the two members of the society:

In "An Empirical Refutation of Pareto-optimality?" Rupert Read argued that the empirical evidence in Wilkinson and Pickett's The Spirit Level suggests "the remarkable normative conclusion of making the Pareto principle, far from the “conservative” device it is often taken to be, a potential agent of radically-egalitarian/socialist distributive justice." I am arguing here that Rapoport's production and exchange model suggest a mathematical demonstration of the same unexpected conclusion.

On Those Clueless Establishment Economists and Free Trade

I was curious what Bernie Sanders meant on Meet the Press yesterday with his line about how it was too late for “establishment economists”. I have never heard of Michael Stumo and I bet neither has Team Bernie. But this claim struck me as silly:

Establishment economists will defend to the death the idea that trade does not destroy jobs. Yes, I’m serious. They believe that. Really. Instead, they say, job losers move into other jobs so there is no net job loss.He goes onto to bash TPP which is not more about protecting patents and less about free trade. But his new research is a great paper by David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson:

Adjustment in local labor markets [after trade liberalization] is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences. Exposed worker experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income. At the national level, employment has fallen in U.S. industries more exposed to import competition, as expected, but offsetting employment gains in other industries have yet to materialize.Autor, Dorn, and Hanson are confirming what anyone familiar with the Stopler-Samuelson theorem would have predicted. Even if these workers found another job – their real wages would fall by more than the price of goods at Wal-Mart. I have no clue who establishment economics may be but those of us who studied international economics were not surprised by these research results. Incidentally this version has a picture that includes Paul Krugman as if he does not understand the Stopler-Samuelson proposition. C’mon man!

Sunday, April 24, 2016

Hysteresis and 9/11

Noah Smith says I got mad at Gerald Friedman. What makes me mad are cheap shots like this:

Honestly why would anyone positively cite Joan Robinson - she literally endorsed the economy of North KoreaIn the 1970’s, there were very few women graduate students seeking Ph.Ds in economics. One of my professors suggested we need more role models like Joan Robinson. I would say his office made me think of what libraries must have looked like in the 19th century except for the fact that it was dominated by papers by Dr. Robinson. She may have been very liberal but she was also a first rate economist. Her The Economics of Imperfect Competition for example should be required reading for all Econ 101ers. But let me get straight to the point by asking what Brad DeLong meant here:

These are principal causes of "hysteresis". I do not believe that the output gap is the zero that the Federal Reserve currently thinks it is. But it is very unlikely to be anywhere near the 12% of GDP needed to support 4%/year real growth through demand along over the next two presidential terms. We could bend the potential growth curve upward slowly and gradually through policies that boosted investment and boosted the rate of innovation. But it would be very difficult indeed to make up all the potential output-growth ground that we have failed to gain during the past decade of the years that the locust hath eatenThe comments from JW Mason to my post indicate a couple of things. He is mad at me and he is also interpreting these lines differently than I do. I will offer an analogy to what Brad was saying that goes back to the fall of 2001, which was very painful for residents of New York City. I bet a lot of my neighbors on the morning of September 12, 2001 wishes they had Brad’s “magic wand” so it would be September 10 with the Twin Towers still standing and those 3000 lost souls still alive. Maybe it was the home run from Mike Piazza but many New Yorkers quickly wanted the rebuilding of the World Trade Center to start very soon. Sure it would take time but then again we had a 1.8% output gap at the end of 2001 according to even perhaps a conservative CBO estimate. And many of us were angry that the politicians took so long to get this rebuilding started. But we did and the World Trade Center is rebuilt. And in the current economy, many of us are saying we need to rebuild the subway system, Penn Station, and even our airports. My complaint with Friedman as well as Mason is that they are claiming liberal economists argue we are at full employment and should not be doing fiscal stimulus. Here is one of JW’s examples:

LMGTFY: http://www.bradford-delong.com/2016/02/no-we-cant-wave-a-magic-demand-wand-now-and-get-the-recovery-we-threw-away-in-2009.html. I'm directly quoting his post. Really, are you incapable of imagining that genuine disagreement is possible on this issue?This is sad as I have noted that there is disagreement on the size of the output gap with Brad noting it may be bigger than others think. Brad also is arguing that aggregate demand stimulus alone could raise the employment to population ratio to 62.5%. So Brad cannot be one of those liberal economists who is arguing we should not do vigorous fiscal stimulus now. Nor can this charge be levied at Krugman, Stiglitz, or Summers. So who are they referring to? Noah notes:

On Twitter, Mason clarified that when he talks about "the people running the show," he meant the Republicans, not Krugman, the Romers, et al.OK! Are these folks those “establishment economists”? If JW is referring to Robert Lucas, the term “liberal” is odd. And if the Federal Reserve is listening to Lucas, I will concede this is a big mistake. In my post, my anger was from the blatant misrepresentation of what others have been saying. I was applauding the efforts to enhance the original Gerald Friedman attempt at analysis. I will just say this. If Bernie Sanders does become President, he is going to need a credible economic model even before we sit down at our next Thanksgiving feast. Waiting until a few graduate students present their findings next summer will not be soon enough. But let me get to what I think Noah’s point was:

Friedman and Mason seem to be arguing that our belief about the facts should be driven, at least in part, by our desire to avoid a feeling of powerlessness. They also seem to be saying that if the facts seem to support conservative policies, even a tiny bit, we should reinterpret the facts. I don't like this approach. It seems anti-rationalist to me, and I think that if wonks behave this way, they'll end up recommending lots of bad policies.This is really a damning comment on the level of that “schlock economics” charge levied at Romer by Lucas. Look – when I was in school, I was told politics is cool. I will admit Bernie Sanders is considered hip, which is fine. Noah is suggesting economists should be nerds, which is likely good advice. Call me a nerd.

Saturday, April 23, 2016

Robert Lucas – Keynesian?

What is a Keynesian? My definition is any economist who recognizes that an insufficiency of aggregate demand can lead to what Paul Krugman dubbed PLOGs – prolonged large output gaps. In the late 1970’s a certain class of macroeconomics called the New Classical school decided we Keynesians were witch doctors practicing junk science. This view dominated certain aspects of academia for 30 years. Krugman’s latest drew a lot of comments from the left but there was one odd one that defended what Robert Lucas wrote back in early 2009. This defense got me to re-read those comments, which included this admission from the dean of the New Classical school:

At the end of 2008, U.S. GDP was about 5 percent below trend. People measure trends in different ways, but 2007 wasn't a great year either. The consensus forecast predicts something like 8 percent below trend by the end of this year.Lucas’s use of “trend” was a bit odd but it is true that the CBO estimate of the output gap at the end of 2008 was 5% and things did get worse in 2009. Some of us are convinced that neither trends nor the CBO is the final word on potential output and I have suggested that 8 years into the Great Recession we still have a 5% output gap. Now that is a PLOG! But let’s give Professor Lucas a little credit for not arguing we never deviate from full employment. His discussion continued by going all Friedman-Schwartz on us as if monetary policy alone could quickly end the output gap. In fact the Bernanke FED did go all Friedman-Schwartz on us with a huge monetary stimulus. Some of us think they should have done more but a lot of the right wing complained it was excessive stimulus. Lucas, however, noted:

I've already said I think what the Fed is now doing is going to be enough to get a reasonably quick recovery committed.OK – this prediction turned out to be quite wrong. But hindsight is 20/20. Lucas slammed Christina Romer for recommending massive fiscal stimulus. There were two parts of this critique:

But, could we do even better with fiscal stimulus? I just don't see this at all. If the government builds a bridge, and then the Fed prints up some money to pay the bridge builders, that's just a monetary policy. We don't need the bridge to do that. We can print up the same amount of money and buy anything with it. So, the only part of the stimulus package that's stimulating is the monetary part. But, if we do build the bridge by taking tax money away from somebody else, and using that to pay the bridge builder -- the guys who work on the bridge -- then it's just a wash. It has no first-starter effect. There's no reason to expect any stimulation. And, in some sense, there's nothing to apply a multiplier to. (Laughs.) You apply a multiplier to the bridge builders, then you've got to apply the same multiplier with a minus sign to the people you taxed to build the bridge. And then taxing them later isn't going to help, we know that.I’m not sure why this right wing crowd laughed but one would have hoped Robert Barro might have whispered to Professor Lucas that he just misrepresented the Barro-Ricardian equivalence proposition. Krugman certainly jumped on this nonsense from Lucas:

think about what happens when a family buys a house with a 30-year mortgage. Suppose that the family takes out a $100,000 home loan (I know, it’s hard to find houses that cheap, but I just want a round number). If the house is newly built, that’s $100,000 of spending that takes place in the economy. But the family has also taken on debt, and will presumably spend less because it knows that it has to pay off that debt. But the debt won’t be paid off all at once — and there’s no reason to expect the family to cut its spending right now by $100,000. Its annual mortgage payment will be something like $6,000, so maybe you would expect a fall in spending by $6000; that offsets only a small fraction of the debt-financed purchase. Now notice that this family is very much like the representative household in a Ricardian equivalence economy, reacting to a deficit financed infrastructure project like Lucas’s bridge; in this case the household really does know that today’s spending will reduce its future disposable income. And even so, its reaction involves very little offset to the initial spending.We needed more fiscal stimulus back in 2009 and we needed to sustain it for longer. We still need a lot of infrastructure investment. In New York City, the good news is that we have decided to spend $4 billion on LaGuardia Airport and another $3 billion on Penn Station. And what we need to spend on our subway system is staggering. But I don’t want to be a selfish New Yorkers here. If there is any concern about deficit spending, let those very rich Republicans on the Upper East Side pay more in taxes to extend the new Second Avenue line to south Manhattan. But let’s get to the part the latest right wing critic of Krugman was noting. Someone asked Lucas the following:

In the last session, we had quite an animated discussion which spilled over into the lunch about models on fiscal multipliers, what they are. On the one extreme, we have models by people like Mark Zandi at Moody's who say that the fiscal multiplier for the spending initiatives we're discussing are on the order of 1.5. On the other hand, we have people like Robert Barro at Harvard who say there's zero or negative. How would you go about applying the Lucas critique to these types of models to sort of educate us in how we should think about the validity of these models?Lucas replied:

It's her first day on the job and somebody says, you've got to come up with a solution to this -- in defense of this fiscal stimulus, which no one told her what it was going to be, and have it by Monday morning. So she scrambled and came up with these multipliers and now they're kind of -- I don't know. So I don't think anyone really believes. These models have never been discussed or debated in a way that that say -- Ellen McGrattan was talking about the way economists use models this morning. These are kind of schlock economics. Maybe there is some multiplier out there that we could measure well but that's not what that paper does.Mark Zandi was McCain’s economic adviser in 2008 who had the good sense to tell the Senator we had a Keynesian problem. Of course the Senator failed to listen to his own economic adviser. Lucas was criticizing Dr. Romer for using Zandi’s model. Now we see criticism from the left for her use of this same model. Go figure! But to be fair – his model is probably best tossed into the waste bin given what we know now. Did I say hindsight is 20/20?

Friday, April 22, 2016

Worstall's Malignant Lump

In an op-ed at the New York Times yesterday, Nick Hanauer and Robert Reich made the following observation:

To be precise, Worstall's assertion is one version of the fallacy claim complex. It happens to be the version refuted by Maurice Dobb in 1929. As Dobb pointed out, workers are concerned with how much compensation they receive in return for the amount of effort required of them and not simply in the aggregate amount of employment in the economy. Working longer hours for less pay is not a bonanza for the workers even if it does lead to more aggregate hours worked in the economy as a whole.

But again, Worstall's fallacy claim is but one version of a complex of claims, some of which contradict each other. I addressed this perplexing proliferation of claims in my contribution to Working Time: International trends, theory and policy perspectives. Refute one of the bogus fallacy claims and a substitute will immediately pop-up to take its place!

It is not easy to unpack what is going on inside the fallacy claim because its persuasive strategy is based on a "house of mirrors" effect. Whether disingenuously or unwittingly, fallacy claimants commit yet another version of the fallacy they attribute to others. Their error, though, is embedded in the perfect competition, perfect information, full employment, ceteris paribus abstractions of the standard equilibrium model of supply and demand. The name given to this set of abstractions by those who mistake them for a description of reality is "economics." When "economists" commit this vulgar error it is regarded by Worstall & Co. as an infallible maxim.

Now, it is conceivable that some of those accused of committing the lump-of-labor fallacy may indeed assume the proverbial "fixed amount of work to be done" or whatever. There can be bad arguments for a good cause. But, as A.C. Pigou pointed out in his refutation of the ubiquitous fallacy claim, "If it were a good ground for rejecting an opinion that many persons entertain it for bad reasons, there would, alas, be few current beliefs left standing!"

In a cruel twist, the longer and harder we work for the same wage, the fewer jobs there are for others, the higher unemployment goes and the more we weaken our own bargaining power. That helps explain why over the last 30 years, corporate profits have doubled from about 6 percent of gross domestic product to about 12 percent, while wages have fallen by almost exactly the same amount.According to Tim Worstall, Hanauer and Reich committed a lump-of-labor fallacy. Worstall objected specifically to their claim that raising the income cap for the overtime premium would force employers to either pay higher wages or hire more workers. Worstall's objection is that the employer's demand for labor will not remain the same if the cost of that labor goes up.

To be precise, Worstall's assertion is one version of the fallacy claim complex. It happens to be the version refuted by Maurice Dobb in 1929. As Dobb pointed out, workers are concerned with how much compensation they receive in return for the amount of effort required of them and not simply in the aggregate amount of employment in the economy. Working longer hours for less pay is not a bonanza for the workers even if it does lead to more aggregate hours worked in the economy as a whole.

But again, Worstall's fallacy claim is but one version of a complex of claims, some of which contradict each other. I addressed this perplexing proliferation of claims in my contribution to Working Time: International trends, theory and policy perspectives. Refute one of the bogus fallacy claims and a substitute will immediately pop-up to take its place!

It is not easy to unpack what is going on inside the fallacy claim because its persuasive strategy is based on a "house of mirrors" effect. Whether disingenuously or unwittingly, fallacy claimants commit yet another version of the fallacy they attribute to others. Their error, though, is embedded in the perfect competition, perfect information, full employment, ceteris paribus abstractions of the standard equilibrium model of supply and demand. The name given to this set of abstractions by those who mistake them for a description of reality is "economics." When "economists" commit this vulgar error it is regarded by Worstall & Co. as an infallible maxim.

Now, it is conceivable that some of those accused of committing the lump-of-labor fallacy may indeed assume the proverbial "fixed amount of work to be done" or whatever. There can be bad arguments for a good cause. But, as A.C. Pigou pointed out in his refutation of the ubiquitous fallacy claim, "If it were a good ground for rejecting an opinion that many persons entertain it for bad reasons, there would, alas, be few current beliefs left standing!"

What Does Krugman Really Think We Should Do To Reduce Carbon Emissions?

Paul Krugman has written what I find to be one of his most confusing posts ever on "101 Boosterism" (or for extended comments on an exceprt see Mark Thoma's link). I agree with his main point, which follows up on a post by Noah Smith, that while Econ 101 often provides useful insights about the world and policy, it can often be misleading because it is not always right, or not as strongly right as many think to the point that for policy purposes it should be ignored. Krugman initially discusses international trade, which I am not going to comment on here, but then shifts to global climate policy with respect to carbon, which I shall, and which is where I think he gets confusing.

His target is carbon pricing, which he thinks is good in theory, 101 theory at least, but not necessarily so good in practice in terms of combating global warming. His example of successful carbon pricing is the US SO2 pricing policy that he accurately describes as having successfully helped reduce acid rain in the US. This was a cap and trade (or "tradeable permits" policy, to use older terminology) program, which has in recent years gotten somewhat messed up. He does not comment directly on Pigovian taxation of carbon emissions, although presumably this would also be in his firing line as a carbon pricing strategy, even though such "prices" are not derived from markets but simply imposed by governments. His general skepticism is that people do not respond sufficiently to carbon pricing signals to really reduce emissions, and he may be right about that.

Instead he proposes that we go after shutting down the use of coal. But that is where he goes all vague. Is this supposed to be a ban on new coal-fired plants, which are not being built anyway in the US at least due to the much lower prices for natural gas ones, or is he proposing actively shutting down currently operating coal-fired power plants, something that is very unlikely to be implemented and could be very expensive and disruptive if done too suddenly? I do not know, although maybe it does not matter. Coal continues to be the leading source of electricity in the US, and its use continues to expand abroad, especially in the important nations of China and India, despite some commitments to get off it, especially by China as part of the Paris agreement. Coal has many other ills and is a more general pollutant than just as a source of CO2, but it really is unclear what Krugman thinks we should do or at what level: US or global, with, as I have noted, coal probably over as an expanding source of energy in the US simply due to the price signals in the energy market in comparison with natural gas.

What he also does not address is the much more perfervid fight now between those advocating Pigovian carbon taxes (or maybe the fee and dividend variation) versus those advocating cap and trade. The former has become very fashionable to the point that many are claiming that nearly all economists favor it with some politicians even turning it into a lame litmus test of whether somebody has progressive views about the issue. Are you or are you not for pricing carbon by putting a tax on emissions, and if not, why not, you dastardly climate-hating swine? I find this attitude highly annoying as well as poorly informed.

While it is probably true that more economists favor taxing carbon emissions than the currently unfashionable cap and trade, the opinion probably is reversed if one looks at environmental economists who have studied this more in depth. There certainly are some prominent economists involved in the global warming issue who support the taxation approach, notably Stiglitz and Nordhaus, both of whom always have. But many others more specialized in the field while less known to the public favor cap and trade, such as Robert Stavins and Tom Tietenberg, with Krugman's position on this unclear, despite his shoutout for the US SO2 cap and trade program.

The hard fact is that cap and trade is by far more in place around the world and is more encouraged by the new Paris agreement, substantially because it is the successor to the Kyoto Protocol, which definitely favored cap and trade, with Europe adopting the policy as a result. There are nations and sub-national regions that have implemented carbon taxes successfully, and this is allowed by the Paris agreement for nations to do in pursuit of achieving agreed on goals. But it must be noted that such taxes are indeed arbitrary in their levels and uncertain in their impacts for the very reasons Krugman has put forward: we do not know how much people will respond and reduce emissions by in response to them.

This is where cap and trade has an advantage. It sets a quantity limit, the cap, and in most nations where it is in place, it has followed a policy that was originally just a quantity limit, which I would think many should favor regarding global carbon emissions. Set an emissions limit so that we know what the emissions will be. However, it moves beyond that to establish a system that if properly managed will achieve the most cost effective way of achieving that emissions limit. I am somewhat mystified why so many think that this is an awful policy as compared to taxes whose emissions impact is not known, and which become very complicated to implement if someone wants to have a coherent policy of this across national boundaries (something rarely mentioned by the advocates of this, but a very real complication).

In any case, I do not know where Krugman stands on this, and maybe he himself does not either. But I certainly think there needs to be more pushback against this mindless current fad for carbon taxation. Some say it can be sold if it is done in a revenue neutral way as was done recently in BC. But in the US the GOP is simply not going to pass anything that is a tax, with their rejection of Obama's effort to establish a cap and trade system for carbon being based on the claim that it was "really" a tax in disguise. I find it amazing that practical people like Joe Stiglitz do not recognize this hard reality.

Barkley Rosser

His target is carbon pricing, which he thinks is good in theory, 101 theory at least, but not necessarily so good in practice in terms of combating global warming. His example of successful carbon pricing is the US SO2 pricing policy that he accurately describes as having successfully helped reduce acid rain in the US. This was a cap and trade (or "tradeable permits" policy, to use older terminology) program, which has in recent years gotten somewhat messed up. He does not comment directly on Pigovian taxation of carbon emissions, although presumably this would also be in his firing line as a carbon pricing strategy, even though such "prices" are not derived from markets but simply imposed by governments. His general skepticism is that people do not respond sufficiently to carbon pricing signals to really reduce emissions, and he may be right about that.

Instead he proposes that we go after shutting down the use of coal. But that is where he goes all vague. Is this supposed to be a ban on new coal-fired plants, which are not being built anyway in the US at least due to the much lower prices for natural gas ones, or is he proposing actively shutting down currently operating coal-fired power plants, something that is very unlikely to be implemented and could be very expensive and disruptive if done too suddenly? I do not know, although maybe it does not matter. Coal continues to be the leading source of electricity in the US, and its use continues to expand abroad, especially in the important nations of China and India, despite some commitments to get off it, especially by China as part of the Paris agreement. Coal has many other ills and is a more general pollutant than just as a source of CO2, but it really is unclear what Krugman thinks we should do or at what level: US or global, with, as I have noted, coal probably over as an expanding source of energy in the US simply due to the price signals in the energy market in comparison with natural gas.

What he also does not address is the much more perfervid fight now between those advocating Pigovian carbon taxes (or maybe the fee and dividend variation) versus those advocating cap and trade. The former has become very fashionable to the point that many are claiming that nearly all economists favor it with some politicians even turning it into a lame litmus test of whether somebody has progressive views about the issue. Are you or are you not for pricing carbon by putting a tax on emissions, and if not, why not, you dastardly climate-hating swine? I find this attitude highly annoying as well as poorly informed.

While it is probably true that more economists favor taxing carbon emissions than the currently unfashionable cap and trade, the opinion probably is reversed if one looks at environmental economists who have studied this more in depth. There certainly are some prominent economists involved in the global warming issue who support the taxation approach, notably Stiglitz and Nordhaus, both of whom always have. But many others more specialized in the field while less known to the public favor cap and trade, such as Robert Stavins and Tom Tietenberg, with Krugman's position on this unclear, despite his shoutout for the US SO2 cap and trade program.

The hard fact is that cap and trade is by far more in place around the world and is more encouraged by the new Paris agreement, substantially because it is the successor to the Kyoto Protocol, which definitely favored cap and trade, with Europe adopting the policy as a result. There are nations and sub-national regions that have implemented carbon taxes successfully, and this is allowed by the Paris agreement for nations to do in pursuit of achieving agreed on goals. But it must be noted that such taxes are indeed arbitrary in their levels and uncertain in their impacts for the very reasons Krugman has put forward: we do not know how much people will respond and reduce emissions by in response to them.

This is where cap and trade has an advantage. It sets a quantity limit, the cap, and in most nations where it is in place, it has followed a policy that was originally just a quantity limit, which I would think many should favor regarding global carbon emissions. Set an emissions limit so that we know what the emissions will be. However, it moves beyond that to establish a system that if properly managed will achieve the most cost effective way of achieving that emissions limit. I am somewhat mystified why so many think that this is an awful policy as compared to taxes whose emissions impact is not known, and which become very complicated to implement if someone wants to have a coherent policy of this across national boundaries (something rarely mentioned by the advocates of this, but a very real complication).

In any case, I do not know where Krugman stands on this, and maybe he himself does not either. But I certainly think there needs to be more pushback against this mindless current fad for carbon taxation. Some say it can be sold if it is done in a revenue neutral way as was done recently in BC. But in the US the GOP is simply not going to pass anything that is a tax, with their rejection of Obama's effort to establish a cap and trade system for carbon being based on the claim that it was "really" a tax in disguise. I find it amazing that practical people like Joe Stiglitz do not recognize this hard reality.

Barkley Rosser

Thursday, April 21, 2016

Friedman-Mason Version 4.0?

I wish Gerald Friedman would stop writing lines like this:

When I conducted an assessment of Senator Bernie Sanders’ economic proposals and found that they could produce robust growth, the negative reaction among powerful liberal economists was swift and vehement…liberal economists have virtually abandoned Keynesian economicsThe claim that economists like Christina and David Romer bought into the New Classical revolution is both absurd and dishonest. Friedman’s “assessment” fell far short of an actual analysis as it only looked at the aggregate demand side. Putting aside whether his multipliers made sense, you cannot do an analysis without at least some consideration of potential output and it how it will grow between now and 2026. Menzie Chinn is a great place to start:

What Is the Assumed Output Gap in the Friedman Projections? Or, “Is current output really 18% below potential output?” … I do not know what the output gap actually used in the Friedman study, as it is not reported….One thing that should be remembered is that the trend line extrapolated from 1984-2007 implies that the output gap as of 2015Q4 is … -18%. A graphical comparison which highlights the implausibility of the -18% output gap is shown below…By way of comparison, the CBO’s estimate is -2.2%... I want to stress that estimating potential GDP and the output gap is a difficult task.Menzie is noting problems with Friedman-Mason Version 1.0 (the paper with no consideration of potential output) and Friedman-Mason Version 2.0, which assumes potential GDP has been growing at a 3.5% clip since the beginning of the century. This bizarre trend line analysis was how Lawrence Kudlow tried to tell us we were having a Bush boom. The reality is that average real GDP growth over the first 7 years of this century was only 2.5% and we ended 2007 near full employment. To his credit J. W. Mason later accepted the premise that potential GDP growth was 2.5% for these years as he noted that the CBO was forecasting this trend to continue through 2015. Friedman-Mason Version 3.0 would therefore suggest that the GDP gap at the end of 2015 was 10% not 18%. Brad DeLong raises this objection:

These are principal causes of "hysteresis". I do not believe that the output gap is the zero that the Federal Reserve currently thinks it is. But it is very unlikely to be anywhere near the 12% of GDP needed to support 4%/year real growth through demand along over the next two presidential terms. We could bend the potential growth curve upward slowly and gradually through policies that boosted investment and boosted the rate of innovation. But it would be very difficult indeed to make up all the potential output-growth ground that we have failed to gain during the past decade of the years that the locust hath eatenAs I read what Brad has been saying, I would put the GDP gap at something closer to 5% rather than 10%. But let’s note how Dr. Friedman ended his latest:

we have a research agenda for many graduate student papers and dissertations. The strength of Verdoorn’s Law associating productivity growth with economic growth rates and the level of labor shortage. The impact of pro-growth government investment policies – including investment in Research and Development as well as investments in roads, bridges, and other public utilities. The investment accelerator and its role in fiscal stimulus, or in theories of secular stagnation. The determinants of changes in labor force participation and the effect of increasing employment opportunities. Responsiveness of immigration, especially undocumented, to labor demand. The sensitivity of US imports to economic growth, an issue complicated by the international role of the dollar.I could get snarky and note that none of this was in his original paper. But is indeed a grand research agenda and I wish Dr. Friedman well as getting a credible analysis together would help in the fall elections as we know that Team Republican will have their analyzes for whatever they are worth. Two Updates: Paul Krugman gets this right:

Only after this was pointed out did they turn to declaring that the standard analysis was all wrong, and that Keynesians like Christina and David Romer are really just neoclassical types.For those of us who participated in the austerity debates, that’s pretty amazing and disheartening. Remember when Robert Lucas accused Christy Romer of corruptly producing “schlock economics to justify government spending?”Now mind you I am not about to criticize Susan Sarandon as my post was not about politics. Rather – I’m disappointed in the latest from J.W. Mason:

Now I don’t think we want to get caught up in the specific strengths or weaknesses of that paper or the plausibility of particular numbers. I think that there are some problems with the paper. If you were to do the same exercise more carefully you would probably come up with lower numbers…Is there good reason to think that a big expansion of public spending could substantially boost GDP and employment?... The position on the other side, the CEA chairs and various other people who’ve been the most vocal critics of these estimates, has been implicitly or explicitly: “This is as good as we can do.” We’re not talking about core macroeconomic policy issues because they’re not a problem right now that we have 5 percent unemployment, which is full employment. The economy is at potential, more or less. There isn’t any aggregate demand problem to solve.There were serious problems with the original paper but I am glad they are admitting the original assessment was on the high side. But we critics do admit we are below full employment and we have been calling for fiscal stimulus. On this score, the latest from J.W. Mason is even more dishonest than the latest from Gerald Friedman. Guys – you do not win a debate by lying about the other side’s position.

Two Things I Learned About Michael Kinsley

The New York Times published a review today of Kinsley’s latest book, Old Age: A Beginner’s Guide. Reading attentively, I learned at least two things about him.

First, he’s an off-the-charts genius whose intellect simply can’t be compared yours or mine. According to the reviewer, “Mr. Kinsley possesses what is probably the most envied journalistic voice of his generation: skeptical, friendly, possessed of an almost Martian intelligence. If we ever do meet Martians, or any alien civilization, he has my vote as the human who should handle Earth’s side of the initial negotiations.”

OK, I’m reading a bit between the lines, assuming the Martians must be really smart to have developed an advanced civilization on such a barren planet. I know; I saw the movie. (Jordanians must be pretty brainy too.) But the review goes on to plead with Kinsley to write more books, a whole shelf of them, before it’s too late.

And the second thing I learned is that Kinsley’s idea for a grand gesture by the Baby Boom generation, before it marches off into the land of assisted living, is to completely retire the government’s fiscal deficit. I haven’t read the book to get the details, but this must mean something like: boomers vote for politicians who will raise taxes enough to buy back the bonds held by, well, some of them and some of their younger relatives. As a last idealistic act, the énragés of 1968 will remove US treasuries from the world’s portfolios. Searching for a heroic sacrifice comparable to waging WWII, Kinsley has hit on the idea of cashing in US bonds and, I suppose, replacing them with bonds from England or Switzerland or wherever.

Very Martian indeed.

First, he’s an off-the-charts genius whose intellect simply can’t be compared yours or mine. According to the reviewer, “Mr. Kinsley possesses what is probably the most envied journalistic voice of his generation: skeptical, friendly, possessed of an almost Martian intelligence. If we ever do meet Martians, or any alien civilization, he has my vote as the human who should handle Earth’s side of the initial negotiations.”

OK, I’m reading a bit between the lines, assuming the Martians must be really smart to have developed an advanced civilization on such a barren planet. I know; I saw the movie. (Jordanians must be pretty brainy too.) But the review goes on to plead with Kinsley to write more books, a whole shelf of them, before it’s too late.

And the second thing I learned is that Kinsley’s idea for a grand gesture by the Baby Boom generation, before it marches off into the land of assisted living, is to completely retire the government’s fiscal deficit. I haven’t read the book to get the details, but this must mean something like: boomers vote for politicians who will raise taxes enough to buy back the bonds held by, well, some of them and some of their younger relatives. As a last idealistic act, the énragés of 1968 will remove US treasuries from the world’s portfolios. Searching for a heroic sacrifice comparable to waging WWII, Kinsley has hit on the idea of cashing in US bonds and, I suppose, replacing them with bonds from England or Switzerland or wherever.

Very Martian indeed.

Tuesday, April 19, 2016

Time Out for Some Hippie Punching

The higher wisdom, as we all know, is that the Left and Right are equally enemies of Truth, which resides somewhere in the enlightened Center. Since we might forget this amid the climate denialism of Republicans, the absurd economic claims of austerians and the like, Eduardo Porter is here to remind us in this morning’s New York Times.

The poster child for liberal anti-scientism is hostility to nuclear power which, we are told, is an essential component of climate change mitigation. This question has been fully resolved by science, and only the Left’s elevation of emotion over reason prevents it from joining the consensus.

Well excuse me. Without going into boring detail, here are a few directions rational thought might take: (1) Nuclear power is way more expensive than the alternatives. (2) Nuclear power’s inflexible output makes it an inefficient supplement to intermittent energy sources like wind and solar. (3) Since its inception, nuclear power has been repeatedly subject to unanticipated safety concerns. It is pure hubris to think that we now know every risk this technology presents to us. (4) Mitigating climate change means keeping fossil fuel in the ground, which is not the same as investing in non-fossil energy sources, since total energy use is not constant.

I guess this makes me anti-science, huh?

Incidentally, the article makes a huge error in claiming that evolution by natural selection operates at too slow a pace to be perceptible by ordinary (non-scientist) humans. The evolution of bacteria and viruses is real-time and crucial. The evolution of crop pests in response to pesticides also occurs right in front of our eyes and is, or ought to be, a major public concern.

If you’re going to punch hippies for being anti-science, you might want to get your science straight first. Just sayin’.

The poster child for liberal anti-scientism is hostility to nuclear power which, we are told, is an essential component of climate change mitigation. This question has been fully resolved by science, and only the Left’s elevation of emotion over reason prevents it from joining the consensus.

Well excuse me. Without going into boring detail, here are a few directions rational thought might take: (1) Nuclear power is way more expensive than the alternatives. (2) Nuclear power’s inflexible output makes it an inefficient supplement to intermittent energy sources like wind and solar. (3) Since its inception, nuclear power has been repeatedly subject to unanticipated safety concerns. It is pure hubris to think that we now know every risk this technology presents to us. (4) Mitigating climate change means keeping fossil fuel in the ground, which is not the same as investing in non-fossil energy sources, since total energy use is not constant.

I guess this makes me anti-science, huh?

Incidentally, the article makes a huge error in claiming that evolution by natural selection operates at too slow a pace to be perceptible by ordinary (non-scientist) humans. The evolution of bacteria and viruses is real-time and crucial. The evolution of crop pests in response to pesticides also occurs right in front of our eyes and is, or ought to be, a major public concern.

If you’re going to punch hippies for being anti-science, you might want to get your science straight first. Just sayin’.

Saturday, April 16, 2016

The Saudi “Threat” to Dump Treasuries

A bill now going through Congress would chip away at Saudi Arabia’s sovereign immunity defense against claims that they abetted the 9/11 terrorists, which they apparently did. The Saudi government, with its tender commitment to due process and human rights, has threatened to retaliate by selling its hoard of US treasuries.

You’d have to be pretty naive to tremble at this. For every sale there has to be a purchase, so the Saudis have to find buyers for these bonds. Presumably the buyers will be those who hold close substitutes (relatively risk-free sovereigns issued by other secure states), who can be induced by a small premium to rebalance their bond portfolio in a dollar-denominated direction. Meanwhile, the Saudis will likely take the cash and purchase these other, non-US, sovereigns. The result will be a slight temporary decrease in the price of treasuries and perhaps a slight easing in the value of the dollar, which would actually be good news for the US economy. (Although my understanding is that most of the actual accounts in which the Saudi-owned treasuries are held are located in London; correct me if I’m wrong.) If the Fed had any concerns about the one-time selling pressure against treasuries it could quantitatively ease by buying a bunch of them itself.

Of course, maybe this is desperation disguised as bluster. With the fall in oil prices, the Saudis may need to liquidate some of their holdings to keep their race horses properly groomed and fed. Why not portray this is a weapon to prevent disclosure of its past deeds?

You’d have to be pretty naive to tremble at this. For every sale there has to be a purchase, so the Saudis have to find buyers for these bonds. Presumably the buyers will be those who hold close substitutes (relatively risk-free sovereigns issued by other secure states), who can be induced by a small premium to rebalance their bond portfolio in a dollar-denominated direction. Meanwhile, the Saudis will likely take the cash and purchase these other, non-US, sovereigns. The result will be a slight temporary decrease in the price of treasuries and perhaps a slight easing in the value of the dollar, which would actually be good news for the US economy. (Although my understanding is that most of the actual accounts in which the Saudi-owned treasuries are held are located in London; correct me if I’m wrong.) If the Fed had any concerns about the one-time selling pressure against treasuries it could quantitatively ease by buying a bunch of them itself.

Of course, maybe this is desperation disguised as bluster. With the fall in oil prices, the Saudis may need to liquidate some of their holdings to keep their race horses properly groomed and fed. Why not portray this is a weapon to prevent disclosure of its past deeds?

Good Jobs for Non-College Grads

It’s good to see that Katherine Newman has spoken up for really investing in kids who aren’t going on to college, which will always be a substantial chunk of them, no matter what. If there’s any sort of social contract worth defending, it has to include them. This means high quality technical programs in high school, staffed by teachers who are well respected and remunerated. Read her op-ed piece.