The temporal aspect is particularly striking,’ writes philosopher Stephen Gardiner, who has done perhaps more than anyone to foreground it, in A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change: it catches us in a bind. Given that global warming is ‘seriously backloaded’ (every moment experiencing a higher temperature posted from the past) and ‘substantially deferred’ (the cumulative effects of current emissions arriving in the future), a warped ethical structure arises. The person who harms others by burning fossil fuels cannot even potentially encounter his victims, because they do not yet exist. Living in the here and now, he reaps all the benefits from the combustion but few of the injuries, which will be suffered by people who are not around and cannot voice their opposition. Each generation, reasons Gardiner, thus faces a perverse incentive to ‘pass the buck’ to the next, which also profits from its own fossil fuel combustion while dodging the pain from it, and so on, in a vicious cycle of infliction of harm.James P. Kossin, "A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed":

As the Earth’s atmosphere warms, the atmospheric circulation changes. These changes vary by region and time of year, but there is evidence that anthropogenic warming causes a general weakening of summertime tropical circulation. Because tropical cyclones are carried along within their ambient environmental wind, there is a plausible a priori expectation that the translation speed of tropical cyclones has slowed with warming. In addition to circulation changes, anthropogenic warming causes increases in atmospheric water-vapour capacity, which are generally expected to increase precipitation rates9. Rain rates near the centres of tropical cyclones are also expected to increase with increasing global temperatures. The amount of tropical-cyclone-related rainfall that any given local area will experience is proportional to the rain rates and inversely proportional to the translation speeds of tropical cyclones.

Here I show that tropical-cyclone translation speed has decreased globally by 10 per cent over the period 1949–2016, which is very likely to have compounded, and possibly dominated, any increases in local rainfall totals that may have occurred as a result of increased tropical-cyclone rain rates. The magnitude of the slowdown varies substantially by region and by latitude, but is generally consistent with expected changes in atmospheric circulation forced by anthropogenic emissions. Of particular importance is the slowdown of 21 per cent and 16 per cent over land areas affected by western North Pacific and North Atlantic tropical cyclones, respectively, and the slowdown of 22 per cent over land areas in the Australian region. The unprecedented rainfall totals associated with the ‘stall’ of Hurricane Harvey over Texas in 2017 provide a notable example of the relationship between regional rainfall amounts and tropical-cyclone translation speed. Any systematic past or future change in the translation speed of tropical cyclones, particularly over land, is therefore highly relevant when considering potential changes in local rainfall totals.

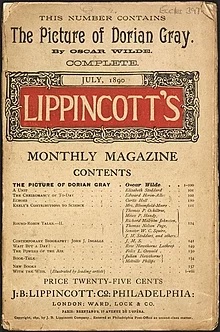

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray:

Even those who had heard the most evil things against him (and from time to time strange rumors about his mode of life crept through London and became the chatter of the clubs) could not believe anything to his dishonor when they saw him. He had always the look of one who had kept himself unspotted from the world. Men who talked grossly became silent when Dorian Gray entered the room. There was something in the purity of his face that rebuked them. His mere presence seemed to recall to them the innocence that they had tarnished. They wondered how one so charming and graceful as he was could have escaped the stain of an age that was at once sordid and sensuous.

He himself, on returning home from one of those mysterious and prolonged absences that gave rise to such strange conjecture among those who were his friends, or thought that they were so, would creep up-stairs to the locked room, open the door with the key that never left him, and stand, with a mirror, in front of the portrait that Basil Hallward had painted of him, looking now at the evil and aging face on the canvas, and now at the fair young face that laughed back at him from the polished glass. The very sharpness of the contrast used to quicken his sense of pleasure. He grew more and more enamoured of his own beauty, more and more interested in the corruption of his own soul. He would examine with minute care, and often with a monstrous and terrible delight, the hideous lines that seared the wrinkling forehead or crawled around the heavy sensual mouth, wondering sometimes which were the more horrible, the signs of sin or the signs of age. He would place his white hands beside the coarse bloated hands of the picture, and smile. He mocked the misshapen body and the failing limbs.